Famous through the mutiny on the Bounty in 1789, one of the most remote places in the world may play a crucial role for future marine resource sustainability. Projected increases in sea surface temperature, ocean acidification and shifts in the current strength in the South Pacific gyre are projected to enlarge tuna populations around the British Overseas Territory of Pitcairn Islands.

These are the findings of a recent study published in Frontiers in Marine Science by scientists with the Sea Around Us, a research initiative at the University of British Columbia and the University of Western Australia.

Under the lead of marine biologist Amy Rose Coghlan, the researchers conducted a review of models that predict the potential impacts of climate change on the area that hosts the world’s largest marine reserve. Then, they contrasted those models with their reconstructed fisheries catch data, which provided an insight into the fish targeted by the community.

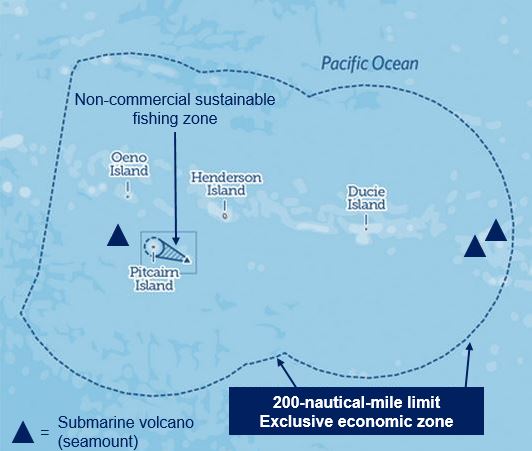

“Projected increases in sea surface temperature are likely to encourage population shifts of pelagic fish such as tuna and sharks towards the marine reserve, which has an area of 830,000 km2. This means that besides preserving near-pristine ecosystems, the reserve has the potential to further act as a refuge for these high-value species,” says Coghlan, who led the study while working as a researcher with the Sea Around Us at UBC’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries.

But there is a flip side to this potential, Coghlan says. “First, these are not the fish that Pitcairn islanders usually eat and they comprise only a small portion of what they sell to visiting cruise ships. Second, while populations of these big fish may increase, climate change may also cause a decline of reef fish and lobsters, which are targeted by Pitcairn fishers.”

Given that only 49 people live on this remote island, and their subsistence catches are only around 4 tonnes a year, the shifts in the distribution of valuable fish could attract industrial fleets, says Dirk Zeller, co-author of the study and lead of the Sea Around Us – Indian Ocean at UWA.

Foreign fishing around the Pitcairn Islands seemed to cease in 2006, but between 1960 and 1980 these waters were occasionally fished by foreign industrial vessels. Currently, there aren’t many commercially valuable species in this region and distances to major markets doesn’t attract much interest. “However, if there is an increase in tuna stocks due to climate change and protection, the story might change. This is why it is so important that such a big area, which is the size of the UK, France and Belgium combined, is already protected from the risk of future industrial exploitation,” Zeller says.

The authors agree that the findings in this study support the numerous calls for the establishment of more marine protected areas that inhibit large-scale fishing operations in big oceanic areas, whilst preserving well-monitored, near-shore reef and deep-water zones that are vital for maintaining domestic coastal fisheries.

The study “Reconstructed Marine Fisheries Catches at a Remote Island Group: Pitcairn Islands (1950–2014)” can be accessed on https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00320