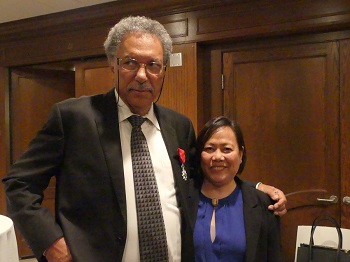

The Sea Around Us’ Deng Palomares and Daniel Pauly have just added a new item to their long list of publications: a chapter in Elsevier’s book Coast and Estuaries: The Future.

In their contribution, titled “Coastal fisheries: the past, present and possible futures,” Palomares and Pauly highlight the importance of coastal fisheries by pointing out that they made up 55 per cent of global marine fisheries catch from 2010 to 2014.

They defined ‘coast’ as the area accessible to small-scale fisheries, meaning, areas at most 50 kilometres from inhabited coastlines or down to a depth of up to 200 metres, whichever comes first.

“This definition describes the ‘inshore fishing area’ (IFA; about 3% of the ocean surface), to which all catches of small scale, that is, artisanal, subsistence, and recreational fisheries are assumed to have been taken,” they explain.

But industrial fisheries also operate within the IFA of various countries, especially in the tropics, and their presence is a common source of conflict with their smaller counterparts. This is particularly the case when massive vessels not only catch a lot, sometimes up to the point where they deplete entire stocks, but also discard big amounts of untargeted, yet edible fish or sell their catch to fishmeal productions plants.

“Meanwhile most of the small-scale fisheries catches are consumed by people and sometimes the fish discarded by industrial vessels is precisely what the small boats would catch. Our analysis shows that 36 per cent of marine catches consumed directly by people between 2010 and 2014 were caught by artisanal, subsistence and recreational fisheries,” Palomares said.

The authors pay special attention to subsistence catches, taken by coastal people in shallow waters or intertidal areas for their own and their family’s consumption, or for bartering against other goods. Based on their examination of these catches, Palomares and Pauly found that they added up to 3.6 million tonnes per year between 2010 and 2014.

“This is an important figure because it is a part of the marine catch that is directly used for consumption by very poor people,” Palomares said. “It is crucial to be aware of this because, particularly in small island developing states in the Pacific and Indian Ocean, these catches are taken by women who contribute directly to the food security of their families.”

In their review, the researchers also describe how the ‘fishing down marine food webs’ process is taking place in coastal areas due to indiscriminate industrial fishing, and how this phenomenon is driving fisheries further offshore, something that small-scale operators cannot do.

With this situation in mind and given the negative effects that climate change is expected to have in fisheries, especially in those around tropical areas, Palomares and Pauly suggest that banning industrial vessels from inshore areas should be a priority for countries wanting to guarantee the survival of their coastal communities.