After the collapse of herring and cod stocks in the western Baltic Sea, flatfish such as plaice, flounder, and dab now dominate the catch. However, they can’t replace the lost catch of cod and herring. Photo by Ilka Thomsen, GEOMAR.

As the abundance of global fish populations continues to deteriorate, top fisheries researchers are calling for simpler yet more accurate stock assessment models that avoid overly optimistic scientific advice, which ends up encouraging overfishing.

In a Perspective Paper published in Science, Dr. Rainer Froese from the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel and Dr. Daniel Pauly from the University of British Columbia’s Sea Around Us initiative, provide insights into a study published in the same journal, in which four Australian research institutions state that while overfishing has long been blamed on fisheries policies setting catch limits higher than scientific recommendations suggest, even such advice has often been too optimistic.

Worldwide, many fish stocks are either threatened by overfishing or have already collapsed. Sea Around Us research has shown that global catches have been declining by 1.2 million tonnes per year since 1996. One key reason for this trend is that policymakers often ignored the maximum catch limits calculated by scientists, which were intended to be strict thresholds to protect stocks. Now, it has become clear that even these suggestions were often too high.

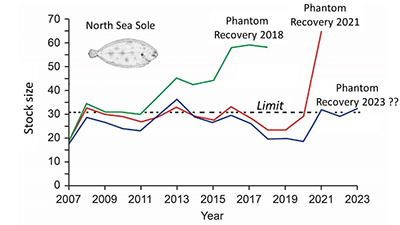

The new study presents data from 230 fish stocks and finds that, even though many are complex and require large amounts of data, most stock assessments overestimated the abundance of fish and how quickly their populations could recover. The overestimations led to so-called ‘phantom recoveries,’ where stocks were classified as recovered while, in reality, they continued to decline.

The image shows, for the North Sea sole, two ‘phantom recoveries’ (2018 and 2021), which later turned out to be non-existent. The incorrect fisheries advice led to continued high catches, preventing real recovery. Source: ICES 2023

“This resulted in insufficient reductions in catch limits when they were most urgently needed,” Dr. Daniel Pauly said. “Unfortunately, this is not just a problem of the past. Known overestimations of stock sizes in recent years are still not being corrected in current stock assessments.”

The research also shows that nearly a third of the stocks classified as “maximally sustainably fished” by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations have instead crossed the threshold into the ‘overfished’ category. Moreover, the number of collapsed stocks, that is, those with less than 10 per cent of their original biomass, within the overfished category is likely 85 per cent higher than previously estimated.

In their Perspective, Froese and Pauly explain that the distortion in stock assessment occurs when the methods employed require multiple parameters and variables that make them unnecessarily complex. Thus, the results can only be reproduced by a few experts – normally in wealthy countries – with access to the original models, data and settings. Moreover, many of the required input parameters are unknown or difficult to estimate, leading modellers to use less reliable values that have worked in the past.

“Such practices can skew the results towards the modellers’ expectations,“ Dr. Froese said.

The authors therefore call for a revision of current stock assessment models. They advocate for simpler, more realistic models based on ecological principles and suggest that, when in doubt, conservative estimates should be used to protect stocks.

“In essence, sustainable fishing is simple,” Dr. Froese said. “Less fish biomass should be taken than is regrown.”

The researchers, who are among the most cited in their field, call for the widespread implementation of ecosystem-based sustainable fishing. This approach proposes that fish must be allowed to reproduce before they are caught; environmentally friendly fishing gear should be used; marine protected areas must be established; and important food chains must be preserved by reducing the catch of forage fish like anchovies, sardines, krill or herring.

“These principles can be implemented even without knowledge of stock sizes,” Dr. Pauly said.

The Perspective Paper “Taking stock of global fisheries. Current stock assessment models overestimate productivity and recovery trajectory” was published in Science, doi: 10.1126/science.adr5487