Industrial fisheries that rely on bottom trawling to catch fish threw 437 million tonnes of fish and $560 billion overboard over the past 65 years, finds new research.

The study documents the growth in bottom trawling, a practice that results in nets full of unwanted or unneeded fish that fishers dump overboard.

“Industrial fisheries do not bring everything they catch to port,” said Tim Cashion, lead author of the study and a researcher with the Sea Around Us initiative at UBC’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries. “During the period we studied, they threw out over 750 million tonnes of fish and 60 per cent of that waste was due to bottom trawlers alone.”

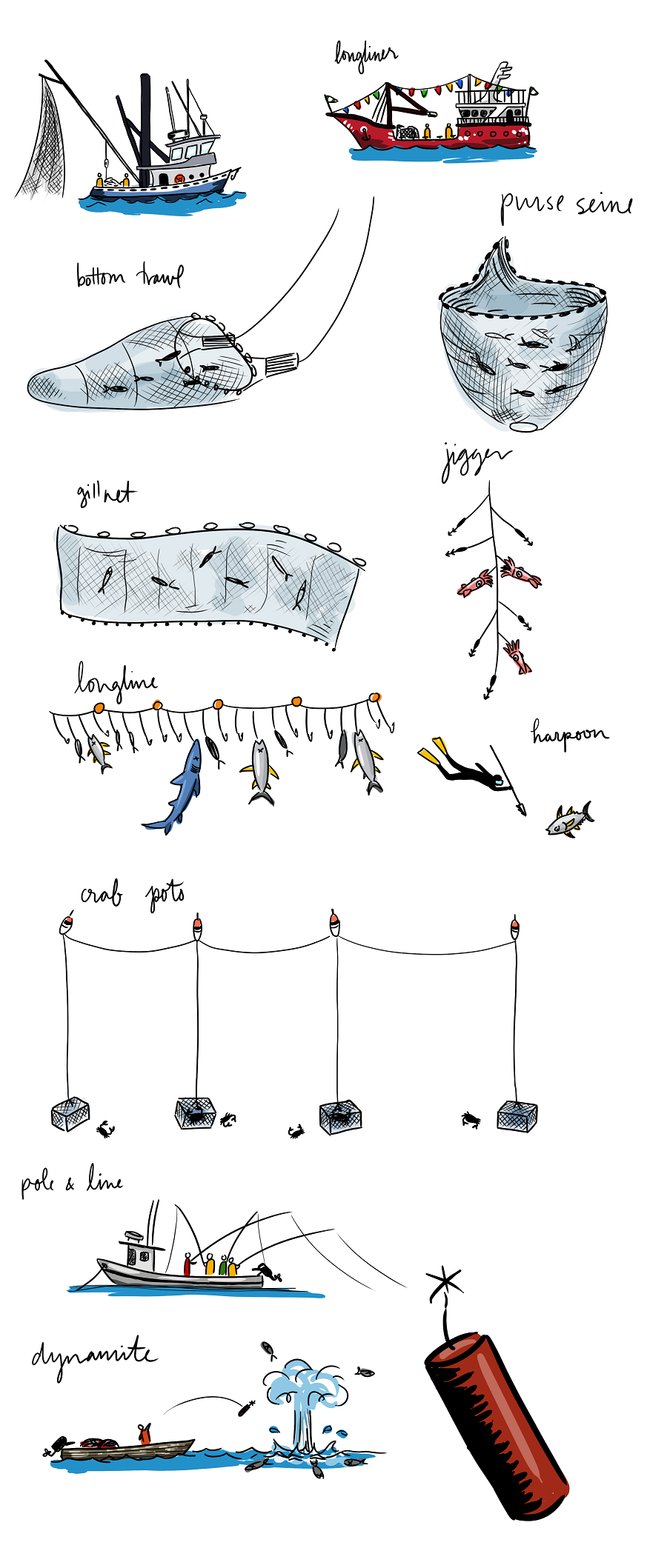

Bottom trawls are large nets that industrial fishing vessels drag along the seabed. They capture everything including deep-sea corals and sponge beds and perfectly good fish but not the ones the fishers are looking for. This fishing method generates the most waste because and the unwanted catch is dumped back into the ocean.

To reach this conclusion, Cashion and his colleagues identified the fishing tools used by industrial and artisanal fisheries in each maritime country and territory and paired them with the millions of records in the Sea Around Us catch database that include reported and unreported catches by fishing country, fishing sector, year and species.

They found that, globally, industrial and artisanal fisheries caught 5.6 billion tonnes of fish in the last six and a half decades. While almost 28 per cent of that catch was captured by industrial bottom trawl, this fishing technique accounts for nearly 60 per cent of fisheries discards.

“They threw away fish that, even though are not the most valuable, are perfectly good for human consumption. Had they landed that catch, they would have made $560 billion according to our prices dataset. The worst part is that, in general, bottom trawlers are so expensive to operate that the only way to keep them afloat is by giving them government subsidies. In other words, it’s a wasteful and inefficient practice,” said Deng Palomares, co-author of the study and the Sea Around Us Project Manager.

Palomares added that, conversely, all small-scale fisheries combined were responsible for only 23 per cent of the global catch or approximately 1.3 billion tonnes in the past 65 year, but their catch was worth significantly more because they use small gillnets, traps, lines, hand tools, and similar utensils to catch specifically what they want.

“Catching fewer quantities of higher-value species, such as crabs and lobsters, they made almost $200 billion.”

According to the researchers, knowing how much fish different fishing tools and techniques remove from specific ocean areas, how much is brought to port and sold and how it’s used, and how much fish is discarded before arriving in port is crucial when it comes to evaluating the costs and benefits of fisheries at national and global levels.

“This information can also be used to boost artisanal fisheries. As the data show, with very little infrastructure and support they already generate more value,” said co-author Daniel Pauly, who is the principal investigator of the Sea Around Us. “If, based on these results, artisanal fisheries received the $35 billion in subsidies that industrial fisheries get every year, they would be able to employ more people than they already do, take better care of their catch, supply specialized markets with a superior product and provide nutritious food for the communities where they operate, all of this while reducing the amount of fish that are discarded or turned into livestock feed.”

The study “Global use of marine fishing gears from 1950 to 2014: Catches and landed values by gear type and sector” was published in Fisheries Research: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165783618301097

To schedule interviews with the authors, contact Valentina Ruiz Leotaud v.ruizleotaud(at)oceans.ubc.ca or call 604.827.3164