A pair of One-spot Pullers (Chromis hypsilepis) preparing to spawn. Home Bommie, Ulladulla, NSW. Photo by Richard Ling, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

In over 80 per cent of fish species, the females, including those known as ‘big old fecund females,’ or BOFFS, grow bigger than the males. This long-established fact is difficult to explain with the conventional view of fish spawning being a drain on the ‘energy’ available for growth. If this view were correct, females, which are defined by their larger reproductive effort, would always remain smaller than males.

This point was emphasized by Daniel Pauly, Principal Investigator of the Sea Around Us initiative at the University of British Columbia’s Institute for the Ocean and Fisheries, in a recent paper published in Trends in Ecology and Evolution. In the article, Pauly stresses that females growing larger than males can be readily explained by the Gill-Oxygen Limitation Theory or GOLT, but not by alternatives relying on a version of the reproductive drain hypothesis.

Though the topic appears to be esoteric, its resolution is important because we are entering an age that will be characterized by the unrelenting warming of the oceans and freshwater bodies. To understand what will happen to marine fish and invertebrates, we need a theory that can explain both why such water-breathing animals remain smaller when they are exposed to higher temperatures and, as well, why the females can grow larger than the males.

Most theories fail to explain both of these phenomena, not to mention other phenomena also explained by the GOLT, which is structured around the simple fact that fish’s gills, as a 2D surface, cannot grow as fast as the 3D bodies they supply with oxygen.

As for the mystery of the larger female, its solution is quite simple: about 90 per cent of the oxygen fish get from their gills is used for various activities and only the rest for growth. Thus, by remaining a bit calmer than the males, females can outgrow them.

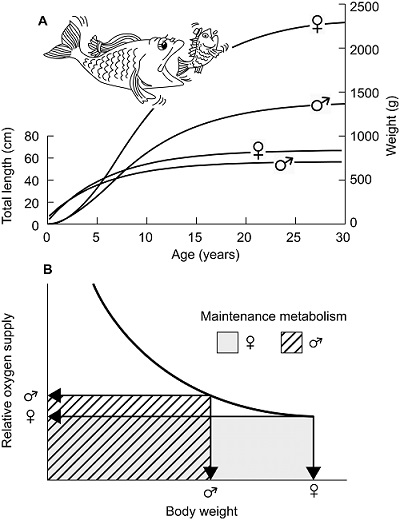

Figure 1. In fishes, it is mostly the females which grow to be big and strong – in spite of their higher reproductive output. This refutes the ‘reproductive drain’ hypothesis. The typical growth curves shown here refers to females and male of European hake (Merluccius merluccius) from the coast of Croatia in terms of length and weight (A; see www.fishbase.org). This is reflected in a plot of their gill area per body weight (and hence relative O2 supply) vs. their body weight, where the better growth of the females is explained by their lower maintenance metabolism, due to a lower rate of activity (B).