Tiger Shark. Image by Kevin Bryant, Flickr.

By Daniel Pauly.

From August 17 to 23, I was in the village of Alpbach in the Austrian Alps, which is, since September 1945 (!), home to an annual gathering of scientists, politicians and other personalities whose mission is to think about European unity, and to make it stronger.

The ‘European Forum Alpbach’ (EFA), as this event is now called, also includes a week during which about 500 people (selected from over 7000 applicants) from European and other countries – PhD students, postdocs, NGO leaders and others – join different seminars to study various topics pertinent to European economic or scientific policies.

I was co-chair, with Professor Kristin Alsdal, a social scientist from the University of Oslo, of a seminar devoted to the Ocean. And yes, I asked for David Attenborough’s film of that title to be shown, which very effectively introduced the point I made, i.e., that Europe’s heavily subsidized distant-water fleets bring havoc wherever they show up, as is well illustrated by the case of Senegal. I also emphasized, when asked what can be done about this, that the best thing one can do is join an environmental NGO and push for sound alternatives to these out-of-control fleets.

One of the participants was Ambre Salmon, from New Caledonia, who responded to my suggestion enthusiastically. But before your read her story, I will mention one small item: I was invited to the EFA based on the recommendation of Cédric Villani, and French ex-politician and top mathematician (see his TED talk) and he took me near midnight to the cemetery of Alpbach, in the back of its church, to see the grave of the physicist Edwin Schrödinger – he of the cat that is both dead and alive at the same time. And behold, somebody had planted a cat statue at Schrödinger’s grave. Cédric told me, though, not to be too excited, because it will probably be stolen; indeed, this cat is regularly stolen – it is there, and not there.

Now to Ambre.

By Ambre Salmon.

New Caledonia is often portrayed as a pristine paradise in the South Pacific. Its lagoon, one of the largest in the world, has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site since 2008 and attracts divers and tourists eager to encounter its vibrant coral reefs and marine life. Yet, beneath this postcard-perfect image lies a growing concern: a surge in shark attacks, particularly along the coast of Bourail, a commune located on New Caledonia’s west coast, about 160 kilometres north of the capital of Nouméa (see map 1). These happenings have unsettled local communities and raised questions about human responsibility in altering marine behaviour.

Between 2010 and 2020, New Caledonia experienced an increase in shark-related incidents, with several tragic outcomes. One of the most traumatic accidents occurred in April 2016 at Poé beach, when a woman was fatally attacked by a tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) just a few meters from shore (Kavo, 2016). Similar incidents followed: in July and October 2020, two swimmers were severely injured in the same lagoon (Peteisi et al, 2020; Cochin, 2020). What makes these attacks striking is that they occurred in shallow waters where sharks are not usually expected. All were attributed to tiger sharks, namely apex predators known for their opportunistic feeding.

According to Philippe Tirard, then a shark specialist at the French research institute IRD, such unusual concentrations of sharks in coastal lagoons may be linked to the presence of “feeding points” created by human activity (Le Point, 2016). Specifically, hunters in the Bourail region have been throwing deer carcasses and offal directly into the sea. These remains act as powerful olfactory stimuli for sharks, which can detect blood and decomposing tissue over vast distances. A 2022 IRD study confirmed that animal remains, fisheries discards, and other organic waste near the coast function as strong attractants for large predatory sharks (Maillaud et al., 2022). In fact, the study estimated that around 18 per cent of all shark attacks recorded in New Caledonia between 1958 and 2020 were linked to such olfactory stimuli.

Evidence supporting this link has been repeatedly observed. In October 2016, a tiger shark fitted with a tracking tag was filmed approaching a deer carcass drifting near Poé (Gallien-Lamarche, 2016). Earlier that year, other carcasses were found near the Cric Salé area, again raising concerns about hunters’ practices (Calédosphère, 2016). These observations reinforced the hypothesis that the rise in attacks was not random but rather linked to the deliberate or careless disposal of hunting remains.

To understand why so many carcasses end up in the lagoon, one must look at New Caledonia’s unique hunting culture. The territory has one of the highest rates of gun ownership in the world, with roughly 37 firearms per 100 inhabitants — a legacy of both rural traditions and the popularity of deer hunting (Ward, 2020). The main target is the rusa deer (Rusa timorensis), a species introduced from Indonesia in the 19th century. With no natural predators and ideal conditions, rusa deer populations exploded, causing significant damage to crops and native ecosystems. Classified as an invasive species, there are no strict limits on hunting them; on the contrary, hunters are encouraged to cull as many as possible (Province Sud, 2020).

Rusa deer. Imabe by Ian Sutton, Flickr.

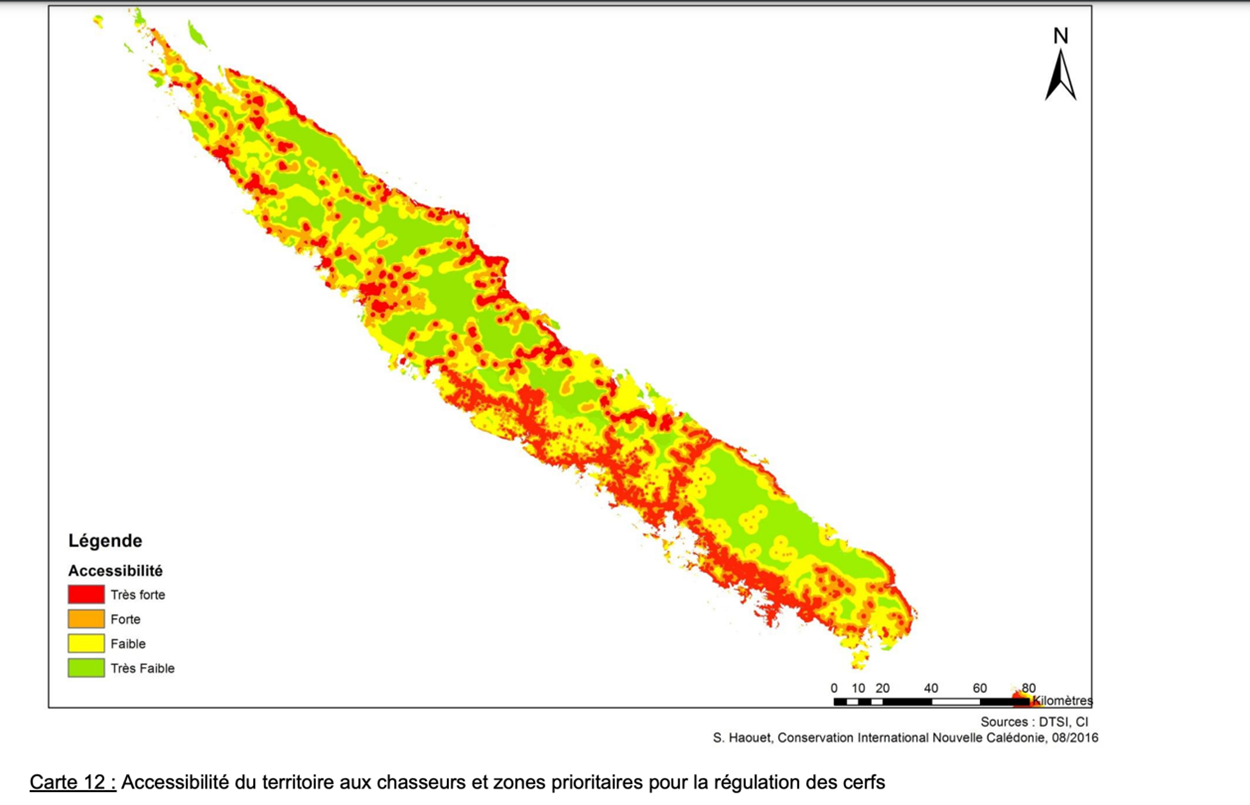

The result is a paradox: while deer hunting helps protect biodiversity on land, the way carcasses are discarded is creating unforeseen consequences at sea. Bourail, the epicentre of several shark incidents, is also one of the areas where deer hunting is most accessible and intense (see map 2). Conservation International data show that this region has the highest accessibility for hunters and is considered a priority zone for deer population control (Espèces Envahissantes Outremer, 2017). This geographic overlap between abundant hunting activity and shark-prone waters makes the link particularly compelling.

Map 2: Accessibility of the territory to hunters and priority areas for deer regulation. Image by Conservation International.

Taken together, these factors suggest that local hunting practices may be inadvertently “conditioning” sharks to approach coastal zones in search of food, thereby increasing the risks for swimmers and divers. While tiger sharks have always been part of New Caledonia’s marine ecosystems, their growing presence close to shore reflects a new dynamic, shaped not by natural cycles but by human behaviour on land.

This issue points to a larger pattern: human activities often extend their influence beyond their intended boundaries. In New Caledonia, decisions made by hunters far from the coastline are reverberating into the lagoon, altering predator behaviour and endangering communities. Addressing this problem does not mean stopping hunting, which remains vital for controlling the invasive deer population, but rather rethinking waste management practices. Alternatives such as designated onshore disposal sites or controlled incineration could help in breaking the link between hunting by-products and shark presence near beaches.

As a New Caledonian myself, born and raised on the island, I grew up with both the pride of our natural heritage and the shock of hearing about shark attacks along our coasts. My studies and work in international cooperation, including on ocean issues, make me particularly aware that this is a crucial moment to reflect on how land and sea are connected. Protecting the lagoon’s image as a safe, living sanctuary depends not only on marine conservation but also on responsible land-based practices. If paradise is to remain paradise, we must recognize that what happens in the forest does not always stay in the forest — sometimes, it swims back to us from the sea.

References:

Calédosphère (2016) Requins à Poé : viandards responsables ? 12 June. Available at: https://caledosphere.com/2016/06/12/requins-a-poe-viandards-responsables/

Cochin, C. (2020) Requin : une attaque à Bourail. France Info – La 1ère, 25 July. Available at: https://la1ere.franceinfo.fr/nouvellecaledonie/province-sud/bourail/requin-une-attaque-907688.html

Especes Envahissantes Outremer (2017) Éléments de cadrage pour une stratégie de régulation des cerfs en Nouvelle-Calédonie. Available at: http://especes-envahissantes-outremer.fr/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/elements-de-cadrage-pour-une-stratgie-de-rgulation-des-cerfs-en-nouvelle-caldonie.pdf

Gallien-Lamarche, J-A. (2016) Un requin bagué attiré par une carcasse à Poé. Les Nouvelles Calédoniennes, 7 October. Available at: https://www.lnc.nc/article/pays/faits-divers/un-requin-bague-attire-par-une-carcasse-a-poe

Kavo, C. (2016) Grave attaque de requin à Poé : la baignade interdite. France Info – La 1ère, 18 April. Available at: https://la1ere.franceinfo.fr/nouvellecaledonie/grave-attaque-de-requin-poe-la-baignade-interdite-348314.html

Le Point (2016) Nouvelle-Calédonie : inquiétude après une attaque mortelle de requin. 18 April. Available at: https://www.lepoint.fr/societe/nouvelle-caledonie-inquietude-apres-une-attaque-mortelle-de-requin-18-04-2016-2033083_23.php

Maillaud, C., Tirard, P., Borsa, P., Guittonneau, A-L., Fournier, J. and Nour, M. (2022) Attaques de requins en Nouvelle-Calédonie de 1958 à 2020 : revue de cas. Marseille: Institut de recherche pour le développement (IRD). Available at: https://ird.hal.science/ird-03570723

Peteisi, M., Rougeau, N. and Poaouteta, N. (2020) Attaque de requin-tigre à Bourail dimanche. France Info – La 1ère, 11 October. Available at: https://la1ere.franceinfo.fr/nouvellecaledonie/province-sud/bourail/attaque-de-requin-tigre-a-bourail-dimanche-895508.html

Province Sud (2020) Guide chasse 2020. Available at: https://www.province-sud.nc/sites/default/files/DDDT/GUIDE-CHASSE-2020.pdf

Ward, S. (2020) New Caledonia has more guns than almost anywhere else on earth. Pacific Island Times, 25 July. Available at: https://www.pacificislandtimes.com/post/new-caledonia-has-more-guns-than-almost-anywhere-else-on-earth