A fresh tuna at a fish market. Photo in the public domain from Rawpixel

Catches of large pelagic fishes such as tunas and sharks in the Indian Ocean are 30 per cent higher than officially reported by the agency in charge of managing these stocks, new research has found.

In a recent paper published in Frontiers in Marine Science, researchers with the Sea Around Us – Indian Ocean initiative and the Marine Futures Lab at the University of Western Australia reconstructed the catches of large pelagic species in the region from 1950 to 2020. They found important gaps in the data reported by the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC) on behalf of its 30 member countries, which mask how much is being extracted to supply the global high-value seafood market.

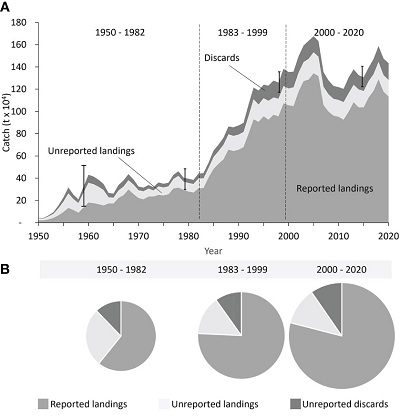

“The Indian Ocean has experienced a steep increase in industrial fisheries for large pelagic species, like albacore and skipjack tuna, over the past 70 years, from 44,000 tonnes a year in the 1950s to 1.4 million tonnes in recent years,” Kristina Heidrich, lead author of the study, said. “Today, the Indian Ocean is home to the world’s second-largest fisheries for large pelagic fishes, which generates annual revenues of around US$6.5 billion. However, we found that a big chunk of what they catch is either discarded at sea or not reported when landed.”

To get a more realistic picture of how much is being taken out of the Indian Ocean, the researchers used the Sea Around Us’ catch reconstruction method, which filled information gaps in the IOTC data with best estimates of unreported catches based on harmonized data from a wide range of sources.

Their results show that unreported landings and unreported discards were caught mainly by distant-water fishing fleets from countries like Taiwan, France and Spain up until the 1980s, and by fleets bearing the flags of Indian Ocean rim countries such as Indonesia, Iran and the Seychelles, in recent years.

“The shift in fishing country flags coincided with the intensification of practices such as reflagging, flag hopping and flag of convenience starting in the 1990s, so we are not convinced that all of these fleets really belong to Indian Ocean countries,” Dirk Zeller, co-author of the study and director of the Sea Around Us – Indian Ocean, said.

“In terms of unreported catches, we noticed that unreported landings and discards are attributable to unselective fishing gears, especially longlines and gillnets, which incidentally catch vulnerable species such as endangered sharks,” Jessica Meeuwig, co-author of the study, Wen Family Chair in Conservation and director of the Marine Futures Lab, said.

Although the IOTC has, since 2011, measures in place that require all members to collect verified catch data, including landings and discards of vulnerable bycatch species, the researchers found that most countries continue to ignore these reporting requirements.

“As a result, both retained and discarded catches are still only partially reported to the Commission,” Heidrich said. “In addition to this, particularly when it comes to sharks, most fisheries do not specify what species are being caught and pool them under a ‘various sharks’ category, or they just report the species identified explicitly by the Commission and do not mention catches of other species. This failure of countries to collect and report detailed fisheries data on sharks and tunas hampers accurate population assessments that can inform management policies.”

The paper “Reconstructing past fisheries catches for large pelagic species in the Indian Ocean” was published in Frontiers in Marine Science https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1177872.