Credit: Christopher Pala

The following story was published in the Inter Press Service News Agency, and is by journalist Christopher Pala.

The original article can be found here.

********************

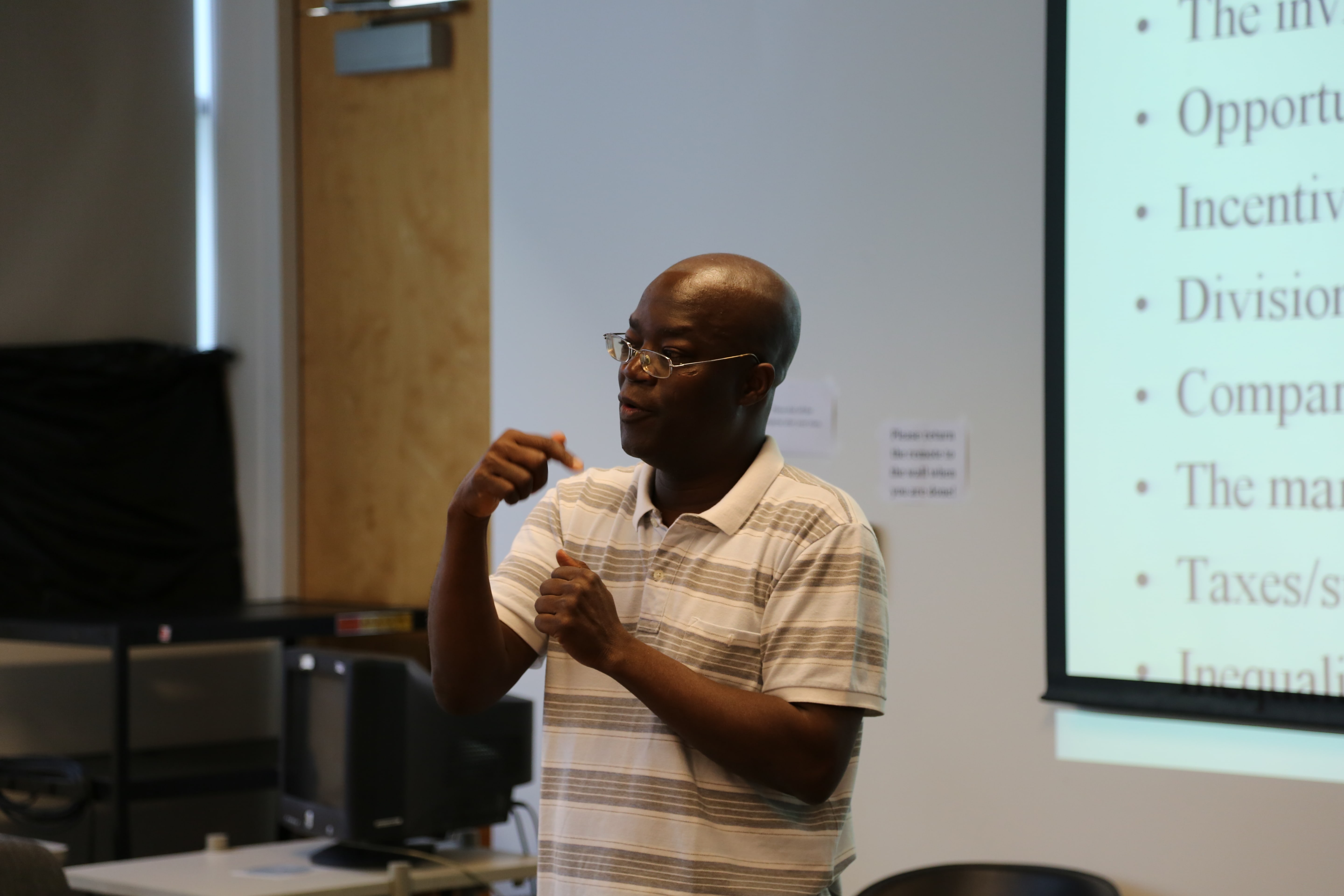

In 2011, Dyhia Belhabib was a volunteer in the Fisheries Centre at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver when she was asked to participate in the Sea Around Us’s project to determine how much fish had been taken out of the world’s oceans since 1950 in order to better avoid depleting the remaining populations of fish.

Belhabib had studied fisheries science in her native Algeria, so she was initially asked to oversee the Algeria component. She ended up leading the research in 24 countries. And though she was an expert and an African, over the next five years, the world of African fisheries took her from surprise to surprise, many of them disquieting, just like Voltaire’s Candide. And echoing Pangloss, who repeats “All is for the best in the best of possible worlds” to a Candide dismayed at the state of the world, the Food and Agriculture Organization insisted the world catch was “practically stable.”

“The most depressing thing for me was the realization that African countries got no benefit at all from all the foreign fleets,” she said. “In fact, the fishing communities suffered a lot, and in most places, the only people who made money were the government officials who sold the fishing licenses.”

The study found that the global catch was 40 percent higher than the FAO reported and is falling at three times the agency’s rate. But under this picture of decline, Belhabib uncovered a dazzling array of cheating methods that highlighted the low priority most governments place on fisheries management – and implicitly on the health of the people who depend on the sea for most of their animal protein.

When Belhabib started with Algeria, she was puzzled to see that the government reported to the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) that between 2001 and 2006, it had fished 2,000 tons of bluefin tuna on average, and yet reported to the FAO that it had caught almost none. Belhabib discovered that for once, the FAO’s zero catch was not a metaphor for “We have no data,” as the study found in many countries. In fact, undeterred by the fact the Algerian fishermen didn’t know how to fish tuna with long-line vessels, the government had simply bought some boats and sold their quotas to countries that did, notably Japan and Italy.

The next country she tackled was Morocco, which took over the Western Sahara in 1975 over the objections of its nomadic people and the international community. The territory has unusually rich waters and two-thirds of Morocco’s catch comes from there. The study estimated the local value of the catch since 1950 at 100 billion dollars, but since it was almost entirely sold in Europe at twice the price, the real value of the catch was 200 billion dollars.

Had the Moroccan government insisted that foreign fleets pay 20 percent of that value, as the EU claims it does today in Morocco (in fact, the study found it pays 5 percent), it could have received a revenue stream of one billion dollars a year, which, had it gone entirely to the Western Sahara, would have doubled the GDP per capita of 2,500 dollars a year for its 500,000 people. Under the current agreement, the EU pays 180 million dollars for access to all of Morocco’s waters, or 120 million dollars for access to the Western Sahara’s waters. How much actually goes to the territory is unclear. Other nations pay far less.

Mauritania has a fleet of locally flagged Russian and Chinese large trawlers that haul in whole schools of small blue-water fish called sardinella. The coast is studded with idle processing plants built to turn them into fish meal, which is used as animal feed. Belhabib discovered that the ships were reporting to the government only a tiny fraction of their actual haul – some of it illegally taken from neighboring countries and selling the rest for higher prices in Europe. “The authorities had no idea,” she said. “They thought their fleet were landing and reporting their whole catch.”

In Senegal, which unlike Mauritania has a strong tradition of fishing, President Macky Sall expelled the Russians in 2012 because their ships had depleted the populations of sardinella, infuriating many Senegalese. “The Russians just got licenses in Guinea Bissau and went back to Senegal and continued to fish, though not as much,” Belhabib said.

The Senegal reconstruction also documented how the European bottom-trawlers severely depleted the country’s near-shore. As population pressure increased demand for cheap fish, the number of artisanal fishermen soared, and many went to work up the coast in Mauritania, where few people fish. But a conflict in 1989 with Mauritania resulted in the expulsion of thousands of Senegalese fishermen, even as the industrial fleets were increasing their catch off both countries, most of it stolen.

Out of desperation, hundreds of Senegalese fishermen and dozens of canoes over the past decade have been boarding Korean and Portuguese converted trawlers that drop them off near the coasts of other countries. There, they illegally drop baited hooks into underwater canyons out of the reach of bottom trawlers where large, high-value fish can still be taken. These spots, marine biologists say, have served as marine reserves, places where coveted, overfished species could reproduce unhindered – and are now being depleted too, pushing the stocks closer to collapse.

Belhabib’s team also discovered to her horror that subsidized European Union fleets had flocked to the waters of countries weakened by civil war, notably Sierra Leone and Liberia, increasing their stolen catch when the people needed cheap protein most.

They found that South Africa made no attempt to control or even report the extensive fishery in the rich waters off its Namibian colony; in 1969, for example, 4.8 million tons of fish worth 6.2 million dollars were caught, but only 13 tons were reported to the FAO. Today, Namibia has the best-managed fishery in Africa after effectively banning foreign-flagged fleets

Finally, examinations of illegal fishing determined that Spain, whose seafood consumption is double the European average, steals more fish than any other nation, followed by China and Japan.