For the first time in over 10 years, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) acknowledged that catch reconstructions, such as those carried out by the Sea Around Us for every maritime country and territory, help fill gaps in national fisheries data and, thus, can illustrate how catches have really changed over time.

In response to this acknowledgement, which appeared in the bi-annual State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture report, known as SOFIA, Daniel Pauly of the Sea Around Us at the University of British Columbia, and Dirk Zeller of the Sea Around Us – Indian Ocean at the University of Western Australia, published a short comment in Marine Policy welcoming what they see as a positive step by FAO in the quest of providing better fisheries data to the global community.

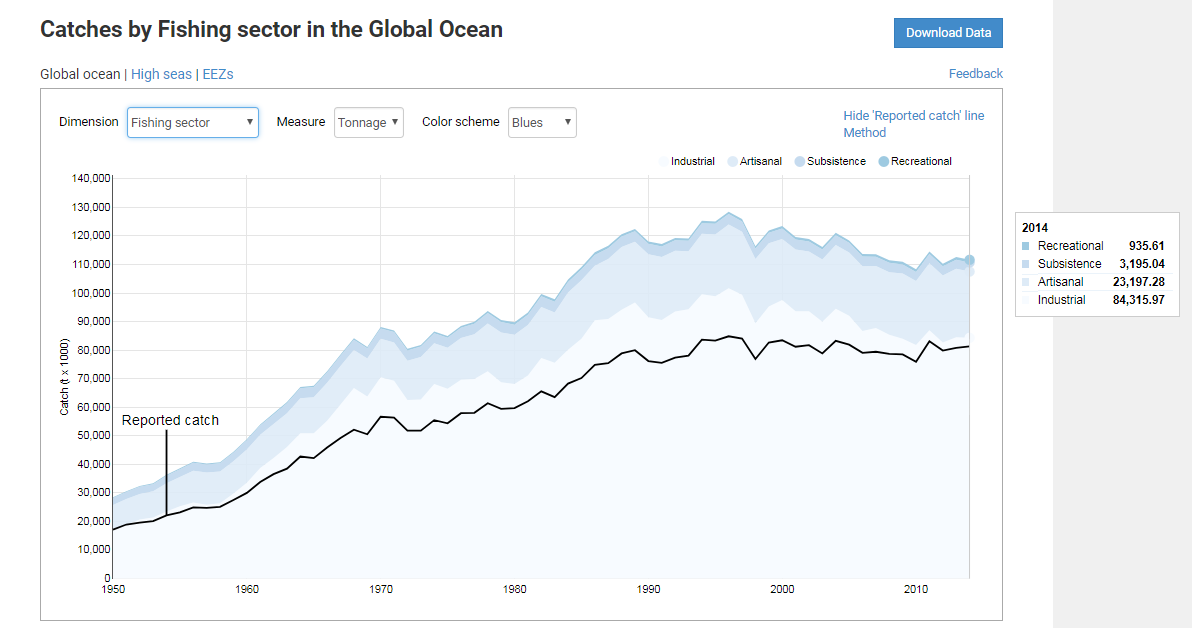

In Pauly and Zeller’s view, identifying that some national statistics, on which FAO relies to create its reports and global policy advice, are incomplete is one of the first positive admissions that the UN agency has made. Many national data are incomplete because they often tend to under-estimate catches from the small-scale sector, such as those of artisanal, subsistence and recreational fisheries.

“We are pleased to see FAO recognising the Sea Around Us’ ongoing call about the importance of drawing attention to small-scale fisheries and reconciling limited budgets with data collection and estimation for this sector that is crucial when it comes to coastal communities’ livelihoods and fundamental food and nutritional security,” Pauly said.

The second major acknowledgment that FAO makes is recognizing that once countries start improving their data collection systems (which is a good thing), they may inadvertently tend to distort their past fisheries statistics because most data improvements are generally focused on present time periods and the future, and do not adequately adjust past data retroactively. This skewing of historical time series data is now known as the ‘presentist bias’ and can lead to overly optimistic time series trends in official statistics.

“This realization is important because the only approach that works against this sort of data bias is, as FAO correctly acknowledges, ‘the backward revision of the catch statistics in the database,’ for example through reconstructions,” Zeller said.

The researchers believe that widening the scope to go beyond predominantly documenting industrial fisheries’ catches and opening the door to new sources of information and expertise, such as collaborations with academia and NGOs, are positive signs of change that are hopefully beginning to take place within FAO. “We welcome and encourage such steps of openness and potential collaboration in the interest of better data for all,” Pauly said.

Read their full letter “Agreeing with FAO: Comments on SOFIA 2018” in Marine Policy, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.12.009