Dr. Daniel Pauly is known these days as the world’s most cited fisheries scientist and the whistleblower who alerted the public about the devastation caused to marine ecosystems by the global fishing industry.

He is the mind behind the idea of the shifting baselines syndrome, which explains how knowledge of environmental disaster fades over time, leading to a misguided understanding of change on our planet, and the fishing down marine food webs concept, which describes how in certain parts of the ocean, fisheries have depleted large predatory fish and are increasingly catching smaller – and previously spurned – species lower in the food web.

These overarching notions have brought him worldwide recognition, as has the creation of FishBase, the online, free encyclopedia of all fish, and the Sea Around Us, a research initiative at UBC’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries (IOF) that has reported massive declines in global fisheries catches in recent years.

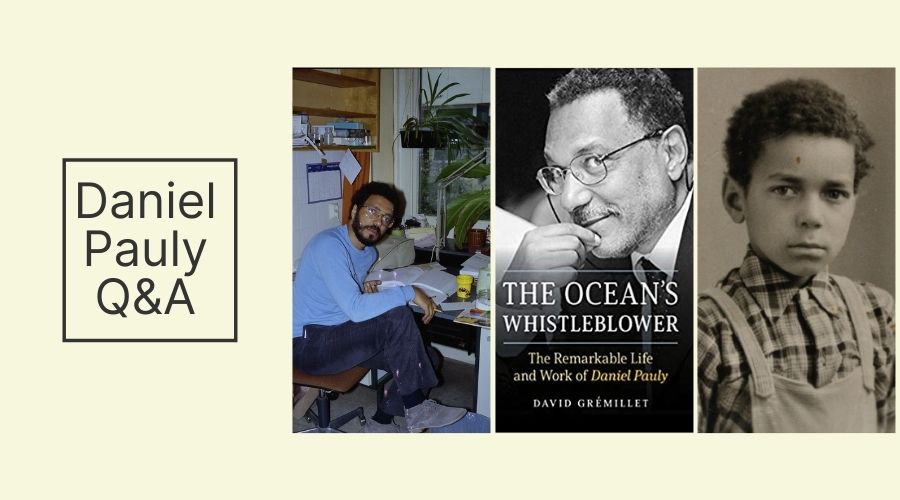

For four decades now, Dr. Pauly’s push for examining fish, fisheries and our seas from a broad perspective has turned him into The Ocean’s Whistleblower, a title that he now shares with a biography written by French marine biologist David Grémillet and whose English edition was released on September 21, 2021.

In addition to laying down Dr. Pauly’s contributions to science and the challenges of global marine research, the book also presents him as a man whose life was shaped by struggle, born in Paris, growing up as a mixed-race child in Switzerland, escaping to Germany from the family that had abducted him from his French mother, putting himself through school, experiencing a political and racial reawakening in the US in the late 1960s, finding his own identity through science and flourishing as a researcher first in the tropics and later on in Canada, where he feels more at home.

Besides presenting your scientific work and how your career has evolved, The Ocean’s Whistleblower delves into intimate details of your life. Why did you decide to share them with the world?

One of the reasons is that I

don’t know how to say ‘no’ and the other thing is for most biographies to be

written, you first have to die and that was not demanded in this case, so that

was nice (laughs).

What was important here was

that this biography not only talked about my difficult youth as a biracial person

in Switzerland and Europe because that would have been a tear-jerker but it also

talks about the science I did.

The biography makes it clear that, given my background, science was a place where I could grow, where I could be. I escaped into science because where I grew up, there were many reasons for me to fall into a hole because the family that raised me were petty criminals. What I ended up doing was developing a stiff spine to resist all that stuff, and since they never made me feel like I was one of them, not doing what they did became a way to build an identity.

Later on, I realized I didn’t

want to live in Europe, where I was constantly questioned about my origins. I

wanted to work in the developing world, and I succeeded in doing that for 20

years. After that, when I came to Canada, I found a respite where I could

continue the work that I began in the Philippines and Indonesia in peace.

So, collaborating on this

book was one way of … (long silence) closing the chapter on what I did while presenting

the science and perhaps motivating other people.

Growing up, you survived by taking odd jobs such as doing quality control at a paint factory or working at a psychiatric hospital. What did you learn in these jobs that you still apply today?

I learned hard work and physically exhausting work. During those days, I

went to high school every weekday from 5 to 9 p.m. after a full day of work. By

the end of the 4-year course, of the 115 students that started, only 15 of us

remained and we made it not because we were smarter, but because we didn’t

think about it. The people who asked themselves every evening, ‘should I go or

not?’, didn’t make it.

This approach is what enabled me, later on in my career, to complete big-data work such as including all known fish species on FishBase or publishing the Global Atlas of Marine Fisheries, which has 400 pages, 273 of which were one-page summaries of the fisheries of all the world’s coastal countries and territories. How does one finish such a monstrous work? Well, you start with one and then you do two, three, four until you finish 273.

In addition to these big-data endeavours, after your first global study on the impact of fisheries, you published the paper “Anecdotes and the shifting baseline syndrome of fisheries” in 1995. You called this a “tiny, little idea” but, nowadays, it has been applied to many fields beyond fisheries and even put you on a TED stage. What makes the shifting baseline concept so universal?

Just as I want to include

everybody in this broad view of fisheries, I apply this to the past, to the

people who wrote stuff 200 years ago. They had eyes to see and brains to think,

and so their contributions ought to be considered. So, I made a point that

observations in the past can be as valid as observations in the present and

that if you ignore trends that have taken place in the past and only look at

trends that have taken place in your lifetime, you will miss the broader

picture.

Shifting baselines is the flipside of adaptation. If we humans liked the past too much, we wouldn’t be able to move forward. Our ability to forget intergenerationally is an adaptive trait that made us very successful as an invasive species. However, that same ability means that we forget about entities – for example, animal species – that disappear. This can be very negative because when you lose something you don’t remember existed, you don’t even try to reestablish it. We are seeing this everywhere on our planet.

Besides this, I think the

article was successful because it was well-written, it was short, and the name

was well-chosen. This naming thing is an important feature in my career, also.

Earlier, I had produced a piece of software that helps estimate the growth and

mortality of fishes, and I called it ELEFAN for Electronic Length Frequency

Analysis. Now, the fact that it was called ELEFAN was clearly one of the

reasons why it was successful; I’m sure because similar software had names like

TX23D, and you could not wrap your mind around the name.

Of all these scientific developments and achievements, what is the one you are most proud of?

Of all the things I have done scientifically, by far, the deepest stuff – different from the broad, global studies – is the theory on oxygen that I developed for my doctoral dissertation. It is also the stuff I have the most problems with.

These days, I’m concentrating on what I call the Gill Oxygen Limitation Theory (GOLT), which didn’t have this name when I first came up with it. It was ‘Pauly’s folly’ or ‘Pauly’s wild theory.’ When I was a student in Germany, there was lots of mockery around me because younger fisheries scientists and graduate students enjoyed working at sea and catching big fish, while I was interested in devising a theory to explain what makes fish grow the way they do.

So, after living in Indonesia and seeing the diversity of fish there, I asked myself: “What enables the big ones to be big and what constrains the small ones?” And I quickly found that the only thing that can produce clear patterns is the growth of the gills, whose surface area differs enormously between fish species.

But what happens to individual fish? The gills are a surface; therefore,

they cannot grow as fast as the body, which is a volume. This means that the

gill area per volume must decline as fish grow and there must be a size at

which they don’t get enough oxygen. This is all self-evident and once you hit

on it, you think, “why don’t people see it?”

During my time in the Philippines, I couldn’t work on the GOLT as much as I wanted, but I continued to think about it and occasionally write about it. After building the Sea Around Us, however, I got young William Cheung as a postdoctoral fellow, and I asked him to develop a model to predict the movements of fish in the context of ocean warming. What I expected was a Volkswagen, and he came up with a Cadillac (laughs). Not only did his model neatly explain why fish move poleward, but he also used my oxygen theory to predict that they will become smaller as ocean temperature increases. Also, he is now the current IOF Director….

So, what I realize now is that global warming is offering my story a huge boost. Basically, ‘Pauly’s folly’ is becoming a significant explanation for what fish do in the face of global warming. It is a sad way to be right.