Bottom trawling in the North Sea . Image by Ifremer.

The 4 billion tonnes of marine organisms that global fisheries extracted from the ocean between 1960 and 2018 resulted in the depletion of over 560 million tonnes of essential nutrients vital to ecosystem health, new research has found.

In a recent paper published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment, researchers at Utah State University and the Sea Around Us initiative at the University of British Columbia estimated that industrial fisheries have removed over 430 million tonnes of carbon, 110 million tonnes of nitrogen, and 23 million tonnes of phosphorus from countries’ exclusive economic zones and 18 high seas regions since 1960.

“Fish and other marine organisms contain specific nutrients in their bodies. By massively targeting 330 species based on consumer demand, sociopolitical factors and natural availability, industrial fisheries have altered the natural nutrient balance of marine ecosystems,” said Adrian Gonzalez Ortiz, who led the research while pursuing his master’s degree at Utah State University. “In other words, the natural flow of nutrients between the different levels of the food web has undoubtedly been changed. Knowing this is important because ocean productivity heavily relies on efficient nutrient recycling.”

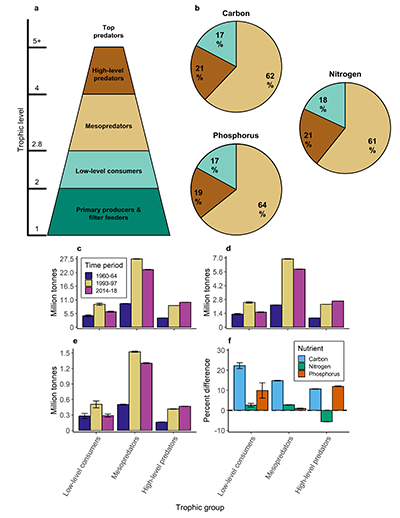

In the past 60 years, most of the nutrient extraction from the ocean occurred through the fishing of medium-sized predators like herring and mackerel – which are both hunters and prey and store high proportions of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous. These were followed by high-level predators like tunas and billfishes, and to a lesser extent by fish in the lower levels of the food chain like sardines and parrotfish.

“On average, the strongly targeted predatory species store higher proportions of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous, compared to other trophic groups,” said Dr. Trisha B. Atwood, co-author of the study and an associate professor at Utah State University. “Disproportionately removing medium-sized predators may diminish the ecosystem’s pool of nutrient-rich biomass and reduce the availability of nutrient-rich prey for higher-level predators. This not only negatively impacts the ecosystem but also fisheries.”

In terms of geography, most of the nutrient extraction occurred in highly productive regions within countries’ Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ), with mid-level predators being the main target and the highest levels of nutrient loss found in the Cambodian EEZ.

Total nutrient extractions by trophic group across time periods. Image from Communications Earth & Environment.

“Although overfishing led to peak catches in the 1990s, the subsequent decline meant that nutrient extraction dropped by half in 160 regions by the 2010s,” said Dr. Maria ‘Deng’ Palomares, co-author of the paper and manager of the Sea Around Us initiative. “Such a decrease in catches resulted in fisheries expanding to other ocean areas, some of these previously unfished. This expansion increased nutrient extractions in recent years in such areas, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions in the Pacific and the high seas.”

In contrast to other studies that have estimated nutrient extraction by using standardized nutrient composition values, this investigation used species-specific measurements of the body content of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous from 330 fishery-targeted species.

“This approach helped us account for the large differences in nutrient content among the various marine organisms targeted by fisheries,” Gonzalez Ortiz said. “Previous studies often overlooked these specificities, but accounting for them is crucial for tracking changes over space and time, and having a more accurate understanding of the impact of losing these nutrients from the ocean.”

The paper “Fisheries disrupt marine nutrient cycles through biomass extraction” was published in Communications Earth & Environment, doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02218-z