Jump to: January, February, March, April, May, June, July, August, September, October, November, December

Category: Contact

The Sea Around Us: A successful trip to Tunisia

Tunisia is the southern Mediterranean country where the events collectively known as the “Arab Spring” started in 2011, and the only country where these events lead to a democratic outcome, for which four major Tunisian political groups recently received the Nobel Peace Prize.

Between late November and early December 2015, Daniel Pauly went to Tunis, the capital of Tunisia, for a period of 5 days, to present lectures and to meet researchers and Tunisian government representatives working on fisheries and marine resources conservation. Dr. Pauly was accompanied by his Tunisian graduate student, Myriam Khalfallah, who co-organized the lectures and the meetings. This visit aimed not only to present the catch reconstruction results for Tunisia and the world, but also to assemble a team of Tunisian experts to improve and update the reconstruction work done for Tunisia. Continue reading

New government aims to protect 10 percent of Canadian coastal waters by 2020

In the Hecate Strait windstorms are frequent, salmon are plentiful, and white stands of silica, called Glass Sponge, cover the ocean floor.

It is a wide, shallow, and stunningly scenic stretch of water that sits between the BC mainland and the islands of Haida Gwaii, and portions of it may soon be protected after a new federal government pledge. Continue reading

China’s Marine Fisheries at a Crossroad: key issues of a forum held in Xiamen, November 10-12, 2015

Forward by Daniel Pauly:

The event held in the modern city of Xiamen, documented below, and at which several colleagues from UBC also participated (William Cheung, Vicky Lam, Mimi Lam, and Tony Picher), was the main reason for my recent trip to China. However, I took this opportunity for a presentation at the very modern Third Oceanographic Institute in Xiamen, and for a one day-visit to Greenpeace China, in their Beijing Headquarters. Greenpeace China has only 4 staff working full time on ocean and fisheries issues, and even though they are motivated and well informed, the challenges they face seem overwhelming. On the other hand, their more numerous colleagues working on energy and pollution clearly face even worse challenges, as evidenced by the foulness of the air on that day. Altogether, a very instructive trip.

Following essay by Yuwei Wang, Xiamen University

From November 10-12, 2015, an international event on “Sustainability of China’s Fisheries [in a] Fast Changing World” was held in Xiamen, Fujian Province, China. The primary goal of this forum, organized by Professor Bin Kang, of Jimei University, was to enable the fisheries, mariculture and marine conservation communities in China to interact with international colleagues. Following a day of formal presentation starting with a keynote by Dr. Daniel Pauly titled “Why reliable catch estimates matter: global comparisons of trends in marine fisheries”, the forum concluded with three workshops, devoted to the issues of each of these communities. I joined the workshop on the management of China’s domestic marine fisheries, which was led by Drs. Daniel Pauly and Chang IK Zhang, an influential researcher from (South) Korea.

Most workshop participants were concerned about the decline of the marine fisheries resources of China, particularly in the East China Sea, which for historical and political reasons, is a very sensitive area. Thus, international cooperation between the three countries exploiting the East China Sea, China, Japan and Korea is required, notably to share data and conduct joint assessments of the stocks they all exploit. Dr. Zhang, building on his broad international experience, strongly argued that a regional fisheries management organization (RFMO) is needed that would coordinate joint research activities and the organize the required data sharing, while maintaining an appropriate degree of confidentiality with regards to sensitive issues.

However, some Chinese researchers pointed out that official data and reports are, in China, kept very distinct from the various datasets gathered and the analyses published by scientists who, moreover, are not provided enough support for them to collect data and perform stock assessments. The workshop participants agreed that this policy of relying exclusively on secret or semi-secret ‘official’ data and reports while ignoring broadly available and vetted scientific data and analyses may have the further decline of Chinese fisheries as outcome.

This bleak prospect is aggravated further by the Government not having earlier engaged with small-scale fishers/boat operators, whose enormous number (and hence fishing power) it is therefore unable to stem, at least currently. Dr. Zhang, in this context, expressed surprise that, in contrast, e.g., to Korea, the majority of Chinese coastal fishers are usually not member of associations. He suggested that in fact, without these fishers being part of association that could control their activities and mitigating the damage they do (indirectly, e.g., through peer pressure) is nearly impossible. It is thus encouraging that the Chinese government has recognized this problem, and has begun, in some provinces, to encourage the self-organization of coastal fishers.

Even if the issues of fisher organization and data reliability were solved, and regular stock assessments were performed for the major resources species, the question of the management regime to adopt would still remain. Should a quota system be introduced in China? How should quota be set and allocated? Should quotas be transferable?

There are successful and failed examples of quota management all around the world. The US quota system appears to work, and its judicious use has led to a rebuilding of previously overexploited stocks on most of that country’s fishing grounds. The quota system also currently works well in Iceland, but it experienced serious disruptions. Iceland has an individual transferable quota (ITQ) system which started in 1990, notably for cod fishing. However, most of these quotas (remember: they were transferable!) were gradually acquired by a Wall Street-based US corporation which went bankrupt in the financial collapse of 2008, thus forcing the Icelandic Parliament to pass legislation to repatriate quotas that should never have left the country.

Dyhia Belhabib in The Gambia

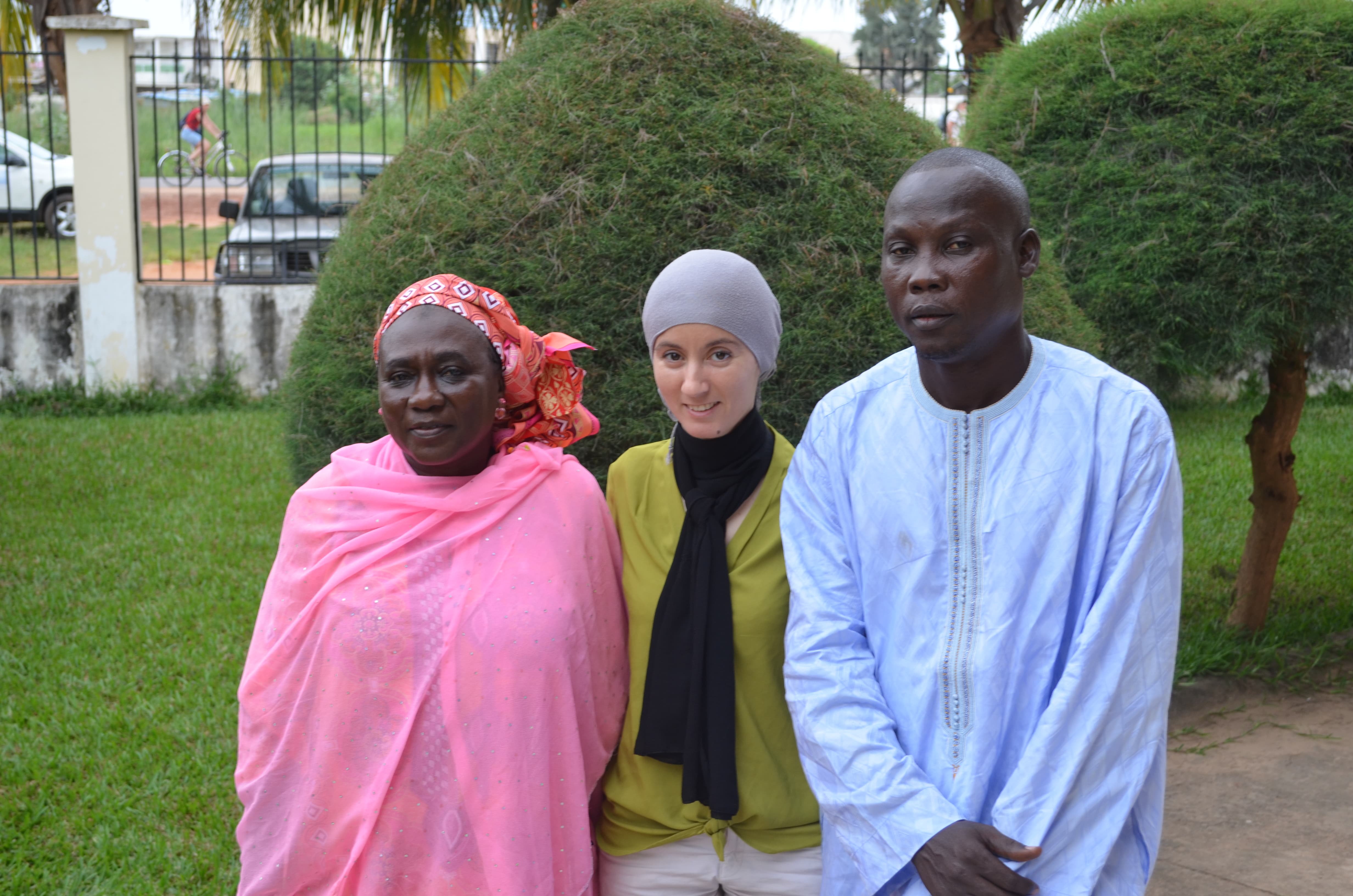

Dyhia Belhabib with Fatima F. Sosseh-Jallow, deputy permanent secretary (DPS), Ministry of Fisheries (on the left), and Ebou Mass Mbye, acting principal Fisheries and head of the Monitoring Control and Surveillance Unit (on the right).

In late November Dyhia Belhabib from the Sea Around Us was in Banjul, The Gambia, to speak at a workshop funded by the MAVA Foundation through the project Sea Around Us in West Africa.

The purpose of the event was to explain catch reconstruction data, the methods behind the data, and to gain feedback from stakeholders in the country.

The room was humid and bustling and was filled with fishers, government representatives, and a host of other organizations eager to discuss the future of fisheries in the country. Dyhia found everyone to be extremely engaged in the conversation.

“There was a lot of participation; everyone in attendance expressed their opinions and their concerns,” she said.

The Gambian government rely on fisheries data to make policy and management decisions, and therefore the quality of the data affects the quality of the decision making.

Fishers, who want their fisheries to be sustainable, suggested they would be able to participate in data collection, to make up for data that sometimes is not available.

“The artisanal fishers wanted to voluntarily report catch data, and they wanted to be taught how to use the logbooks,” said Dyhia.

In addition to the fishers’ keen interest in reporting data, the government stated that they would provide additional agents to travel to fishing regions and help collect data.

“So on the one hand you have a government that is willing to spend effort to collect data, and on the other side, you have the fishers who are willing to provide the data themselves,” said Dyhia.

Ebou Mass Mbye, acting Principal of Fisheries in The Gambia, stressed the importance of reliable and comprehensive information for fisheries sector management. As reported in the Daily Observer, a major newspaper in The Gambia:

“He sincerely hoped that this one day workshop would be successful and would lead to better knowledge and understanding of catch reconstructions.”

Dyhia believes the workshop went a long way in educating the various fishers, NGO’s and government officials in attendance.

“It was great – I was not expecting so much positive feedback,” she said.

For more information read an article about the Sea Around Us in the Daily Observer, a media outlet in The Gambia.