Labour and human rights abuses, overfishing, unreported, unregulated and illegal fishing, all spurred by subsidies provided to distant-water fishing fleets, are some of the most pervasive practices linked to the global seafood industry.

Witnessing and reporting on all of this are fisheries observers. Often scientists – marine biologists or ecologists –, fisheries observers are tasked by national frameworks, regional bodies, or international fisheries organizations with gathering information that supports sustainable fisheries management. Some are hired by the fishing companies they monitor.

Often attracted to the job by the lure of a life at sea or the steady income, fisheries observers live and work on industrial fishing vessels for months at a time, sharing spaces, routines, meals, and entertainment with the same people they’re reporting on. Nothing further from a ‘sweet gig.’ Often, they are killed at sea.

- Keith Davis, from the United States, disappeared while at sea on a Taiwanese-owned, Panamanian-flagged vessel in 2015.

- James Numbaru Jr., from Papua New Guinea, went overboard from a Chinese-flagged vessel in 2017.

- Emmanuel Essien, from Ghana, disappeared from a Chinese-owned vessel in 2019.

- Eritara Aati Kaierua, from Kiribati, died on a Taiwanese-flagged vessel in 2020.

- Samuel Abayateye, from Ghana, went missing from a South Korean-owned vessel in 2023.

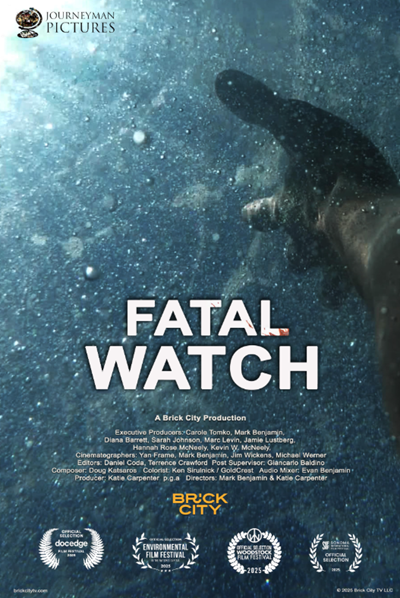

These five cases and their connection to unregulated fishing practices, particularly overfishing, are explored through interviews with investigators probing the industry, researchers, family testimonies, and security-camera footage in the 2025 documentary Fatal Watch, directed by Katie Carpenter and Mark Benjamin

The Sea Around Us PI, Dr. Daniel Pauly, and Australian ichthyologist, Dr. Patricia J. Kailola, are interviewed in the film.

Dr. Kailola recently wrote a review/explainer of the film, which we reproduce below:

This film needed to be made.

Because all over the world people eat tuna – either fresh, or – more usually – as the convenience food: cooked, flavoured, and ready-to-eat in a can. Millions and millions of cans of tuna, representing almost as many living fish.

Tuna are oceanic, pelagic fish; they are caught by a variety of methods, from deep-water handlining, seining, and pole-and-line to industrial-level purse-seine and longline. Thousands of vessels go in search of tuna in all of the world’s oceans – Why? Because there is money to be made from them, lots and lots of money. In the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, for example, USD 2.6 billion-worth of tuna is harvested and sold on world markets each year.

In contrast to land-based resources, offshore fishing activity is not witnessed (ipso facto – it takes place offshore) – so fisheries observers are engaged by regional fisheries management organisations (RFMOs) wherever possible, to ensure that vessels are licensed and adhere to RFMO rules and regulations: to ‘keep the bastards honest’ by independently recording catches and monitoring the vessel captains’ compilation of log-book, avoidance of protected species, maintenance of quota, crew interactions, and so on. Observers are included in the vessels’ complements and are paid by the RFMOs.

Between a rock and a hard place

Observers are not AI models or from outer space: they are human.

Some fisheries (such as the WCPO purse seine fishery) have 100 per cent observer coverage, and not irregularly by two observers, on the same vessel. In contrast, the WCPO longline fishery will only accept 5 per cent of observer coverage – Something unspoken: the power of the money in the fishery emasculates the rules-maker, the RFMO.

Under that shadow, observers are recruited to be just that – independent observers. Yet, their position is compromised because they are in the care of the very person (the captain) whose activity they are obliged to observe: on the one hand, they have signed a contract and are obliged to observe and report, but on the other… they need to survive.

This film most graphically highlights that issue: among others, Essen and Kaierua stuck to their job descriptions and their perceptions of honesty and ‘what is right’ – but as the film identifies, there was only death and post-mortem honour there.

For a lone fishery observer to ‘waver’ in the face of threats from a captain and 20 crew on a vessel 100 nautical miles from land and on the High Seas, where nominal assistance could only come from a satellite phone call days after the event– Who in his air-conditioned land-based office will throw the first stone?

Does Fatal Watch have a moral?

Only in so much as it reveals the variety of human nature (from immense greed to unwavering honesty).

Does Fatal Watch have a lesson?

Fisheries observers are the media attempting to ensure that there will always be tuna in the ocean and on our plates. While protecting them when they are at work is impossible, we consumers are obligated to ‘call out’ the bad actors in the fishery and demand independent results and severe penalties when breaches are realised. And to do that, consumers need to be informed.

Fatal Watch is, thus, a must-see film for all right-thinking people: it informs. The producers and directors have met a considerable challenge with sound hearts, skill and determination. Thoroughly recommended, especially for secondary and tertiary school students and teachers.