Factions among the fisheries community disagree on whether catch data – the amount of fish drawn from the sea – can be used to assess the health of fish stocks. In a comment piece published in Nature today, the Sea Around Us Project’s Principal Investigator Daniel Pauly shares his views, emphasizing that catch data are often the only type of data we have to tell anything about the status of fisheries.

Factions among the fisheries community disagree on whether catch data – the amount of fish drawn from the sea – can be used to assess the health of fish stocks. In a comment piece published in Nature today, the Sea Around Us Project’s Principal Investigator Daniel Pauly shares his views, emphasizing that catch data are often the only type of data we have to tell anything about the status of fisheries.

While developed countries such as the US, Australia and those in Europe are able to use a variety of data, such as size, growth and migration information, as well as survey data, to conduct expert stock assessments, Pauly points out that these come at a cost: anywhere from US$50,000 to millions of dollars per stock. Such costs are not feasible for the majority of developing countries. Furthermore, for 80% of maritime countries, catch is the only data available.

In a second comment piece, Ray Hilborn and Trevor Branch from the School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, University of Washington, argue that there are other factors beyond the health of a fish stock that can account for changes in catch. Used on their own, catch data can create confusion and alarm about the abundance of fish stocks, they say.

Pauly agrees that catch data should be used with caution, but adds there is danger in undermining the value of this information. In most countries, the amount of fish caught is the only information available to assess stock health. “If resource-starved governments in developing countries come to think that catch data are of limited use, the world will not see more stock assessments; catch data will just stop being collected,” says Pauly.

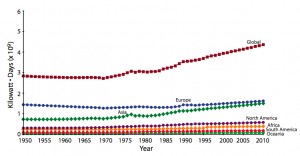

The Sea Around Us Project, under the guidance of Pauly, is currently conducting a global evaluation of catch data, from 1950 to present, collated by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. Results so far reveal that many countries have underreported their catches. The extent of the underreporting is larger in developing countries (about 100-500%; Zeller et al. 2007) than in developed ones (30-50%; Zeller et al. 2011).

To see the full article, please go online to Nature.com: Pauly D (2013) Comment: Does catch reflect abundance? Yes, it is a crucial signal. Nature 494: 303-305.

Zeller D, Booth S, Davis G and Pauly D (2007) Re-estimation of small-scale fisheries catches for U.S. flag island areas in the Western Pacific: The last 50 years. Fishery Bulletin 105: 266-277.

Zeller D, Rossing P, Harper S, Persson L, Booth S and Pauly D (2011) The Baltic Sea: estimates of total fisheries removals 1950-2007. Fisheries Research 108: 356-363.

The new

The new