Fisheries catches in the Arctic totaled 950,000 tonnes from 1950 to 2006, almost 75 times the amount reported to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) during this period, according to a new Sea Around Us led study out this week in Polar Biology. The Arctic is one of the last and most extensive ocean wilderness areas in the world. The extent of the sea ice in the region has declined in recent years due to climate change, raising concerns over loss of biodiversity as well as the expansion of industrial fisheries into this area. This study offers a more accurate baseline against which to monitor changes in fish catches and to inform policy and conservation efforts. Find the full press release that accompanies the research here and coverage in Nature News here.

Fisheries catches in the Arctic totaled 950,000 tonnes from 1950 to 2006, almost 75 times the amount reported to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) during this period, according to a new Sea Around Us led study out this week in Polar Biology. The Arctic is one of the last and most extensive ocean wilderness areas in the world. The extent of the sea ice in the region has declined in recent years due to climate change, raising concerns over loss of biodiversity as well as the expansion of industrial fisheries into this area. This study offers a more accurate baseline against which to monitor changes in fish catches and to inform policy and conservation efforts. Find the full press release that accompanies the research here and coverage in Nature News here.

Category: New Research

Global fishing effort increasing and underestimated

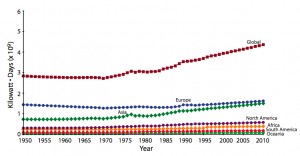

A new study by Sea Around Us Project members examines the global trends in fishing effort from 1950 to 2006 using FAO fisheries data. The analysis confirmed global fishing effort is increasing and that effort is led by Europe and Asia. Trawlers contribute a major fraction of global fishing effort, as do vessels greater than 100 gross registered tons. But the study also notes that there are many limitations to the data, such as the absence of effort data for many countries and the issue of illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing. This means that the World Bank estimate of $50 billion in fisheries losses due to overcapacity is conservative.

A new study by Sea Around Us Project members examines the global trends in fishing effort from 1950 to 2006 using FAO fisheries data. The analysis confirmed global fishing effort is increasing and that effort is led by Europe and Asia. Trawlers contribute a major fraction of global fishing effort, as do vessels greater than 100 gross registered tons. But the study also notes that there are many limitations to the data, such as the absence of effort data for many countries and the issue of illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing. This means that the World Bank estimate of $50 billion in fisheries losses due to overcapacity is conservative.

Full citation: Anticamara, J.A., R. Watson, A. Gelchu and D. Pauly. 2011. Global fishing effort (1950-2010): Trends, gaps, and implications. Fisheries Research 107: 131-136.

New Study Quantifies Expansion of Fisheries

While it is widely-recognized that fishing boats have moved further offshore and deeper in the hunt for seafood, the Sea Around Us Project, in collaboration with the National Geographic Society, recently published in PloS ONE the first study to quantify global fisheries expansion.

While it is widely-recognized that fishing boats have moved further offshore and deeper in the hunt for seafood, the Sea Around Us Project, in collaboration with the National Geographic Society, recently published in PloS ONE the first study to quantify global fisheries expansion.

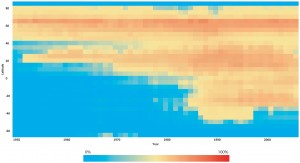

The study reveals that fisheries expanded at a rate of one million sq. kilometres per year from the 1950s to the end of the 1970s. The rate of expansion more than tripled in the 1980s and early 1990s – to roughly the size of Brazil’s Amazon rain forest every year.

Between 1950 and 2005, the spatial expansion of fisheries started from the coastal waters off the North Atlantic and Northwest Pacific, reached into the high seas and southward into the Southern Hemisphere at a rate of almost one degree latitude per year. It was accompanied by a nearly five-fold increase in catch, from 19 million tonnes in 1950, to a peak of 90 million tonnes in the late 1980s, and dropping to 87 million tonnes in 2005. Now we have run out of room to expand fisheries.

The image here (click to enlarge) shows a time series of areas exploited by marine fisheries by latitude class, expressed as a percentage of the total ocean area.

Understanding impacts of the Gulf of Mexico oil spill: How will fisheries fare?

As devastating images of oil in the Gulf of Mexico streamed across virtually every media outlet during the months following the explosion of the Deepwater Horizon on April 20th, 2010, many experts in the fields of marine ecology and fisheries science have found themselves faced with the question, “What will be the impacts of this disaster?” As a native of South Florida with memories of family vacations to Gulf-coast beaches and an appreciation for delicious Gulf seafood, I have been eager to participate in any efforts to better understand the problem.

As devastating images of oil in the Gulf of Mexico streamed across virtually every media outlet during the months following the explosion of the Deepwater Horizon on April 20th, 2010, many experts in the fields of marine ecology and fisheries science have found themselves faced with the question, “What will be the impacts of this disaster?” As a native of South Florida with memories of family vacations to Gulf-coast beaches and an appreciation for delicious Gulf seafood, I have been eager to participate in any efforts to better understand the problem.

Attempting to answer this question is no simple task. Estimates of the quantity of oil, natural gas and associated methane, and chemical dispersants released into the Gulf of Mexico are plagued by uncertainty. The U.S. government-appointed team of scientists, a.k.a. the Flow Rate Technical Group, estimated that a total of 4.9 million barrels of oil were released from BP’s Macondo well [1] while an independent study suggested between 4.16 and 6.24 million barrels [2]. According to BP’s records, approximately 1.8 million gallons (i.e., about 6.8 million litres) of dispersant were applied at the site of the leak as well as the sea surface, though the validity of this amount has been questioned [3]. Complex oceanographic processes have made it extremely difficult to determine the current and future distribution of these toxic substances from the surface to the sea floor, and the duration of their persistence in the marine environment. Most importantly, there are no immediate answers to questions concerning short- and long-term impacts on habitats and marine organisms in the path of this disaster. This uncertainty is particularly troubling for fisheries dependent on economically valuable species.

Despite the geographic distance separating the Fisheries Centre from the Gulf of Mexico, the databases developed by the Sea Around Us Project provide a unique opportunity to explore potential effects of the spill on commercial fisheries in this Large Marine Ecosystem (LME). While these databases supply detailed information on a global scale, they may be easily queried to understand trends occurring in smaller geographic regions, such as the Gulf of Mexico. Using data detailing the location and quantity of species reportedly caught by fishers throughout the Gulf [4], in addition to information regarding the price that they receive when they sell their catch [5], spatial maps illustrating recent trends in catch and landed value were generated for this study.

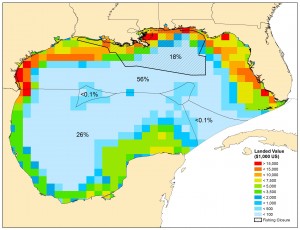

From 2000 to 2005, an average of approximately 850,000 tonnes of fish, crustaceans, molluscs and other invertebrates, primarily inhabiting the highly productive continental shelf area, were commercially caught in the Gulf of Mexico. The majority of this catch originated within the 200 nautical mile limit of the United States’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), followed by landings within Mexican waters. The total landed value of this catch was estimated at approximately $1.38 billion US.

As oil slicks visible on the sea surface grew in size following the spill, the U.S. National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), as well as the States of Florida, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, declared portions of federal and state waters closed to commercial fishing in an effort to promote seafood safety and ensure consumer confidence. The location of this closed area in relation to mapped average catch and landed value was analyzed to provide clues regarding potential economic losses to commercial fisheries in the region.

As of July 22, 2010, over 10% of the total surface area of the Gulf and nearly 25% of the US Gulf EEZ was closed to commercial fishing operations. Figure 2 demonstrates that this closure overlapped with highly productive and economically valuable shelf habitats accounting for 18% of the total annual value of reported commercial landings within the Gulf of Mexico LME. This represents a potential annual loss of $247 million to be suffered by U.S. commercial fishers. While the majority of US catch within the closed area during 2000 to 2005 was composed of Gulf menhaden, landings of brown and white shrimp generated the greatest value (12% of the annual US total in the Gulf, combined) due to high consumer demand and associated prices, followed by blue crabs (4%), Gulf menhaden (3%), and eastern oysters (1%). Potential impacts on valuable invertebrate fisheries may be compounded by the fact that relatively immobile, benthic organisms are likely to suffer higher rates of mortality as a result of the toxic effects of oil compared to more mobile fish species [6]. In addition, the capacity of habitats and species to recover from the effects of oil, methane, and dispersants may have already been compromised due to pre-existing sources of stress, including nutrient-laden freshwater discharge from the Mississippi River resulting in periodic oxygen-depleted ‘dead zones’, and bottom habitat destruction due to extensive shrimp trawling.

While this study does not attempt to address the full range of biological and economic consequences of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on fisheries in the Gulf of Mexico, it does provide a preliminary perspective on one aspect of the puzzle, given pre-oil spill trends. It is evident that the oil spill has clearly impacted an area of crucial economic importance within the Gulf of Mexico.

During the months following the spill, my head has been filled with nostalgic thoughts of flour-like sand squeaking beneath my feet while playing on the beaches of Seaside, Florida, hours spent searching the seashore in Captiva for the beautiful shells that still sit in a bowl in my living room, and devouring a 10 lb bag of steamed clams bought from a fishers by the side of the road in Cedar Key. How will future generations of vacationing families, Gulf-coast residents and fishers remember this region? Hopefully, expectations of environmental resilience along with a continued dedication to clean-up operations will facilitate a swift recovery.

References:

1.http://www.restorethegulf.gov/release/2010/08/02/us-scientific-teams-refine-estimates-oil-flow-bps-well-prior-capping

2. Crone TJ, Tolstoy M (2010) Magnitude of the 2010 Gulf of Mexico Oil Leak. Science 330:634.

3. http://www.ens-newswire.com/ens/aug2010/2010-08-02-091.html

4. Watson R, Kitchingman A, Gelchu A, Pauly D(2004) Mapping global fisheries: sharpening our focus. Fish and Fisheries 5: 168-177.

5. Sumaila R, Marsden AD, Watson R, Pauly D (2007) A global ex-vessel fish price database: construction and applications. Journal of Bioeconomics 9: 39-51.

6. Teal JM, Howarth RW (1984) Oil spill studies: a review of ecological effects. Environmental Management 8: 27-44.

Figure: Spatial distribution of the average (2000-2005) annual landed value of reported commercial fisheries catches in the Gulf of Mexico LME. The area closed to commercial fishing (including both federal and state within the US EEZ as of July 22nd 2010) accounts for approximately 18% of the total value of landings within the LME. The remainder of the US EEZ still open to fishing accounts for 56%, while Mexican waters account for 26% of total landed value. Less than 0.1% of the annual landed value is derived from the two High Seas areas and Cuban waters.

This article written by Sea Around Us post-doctoral fellow Ashley McCrea-Strub and appears in the newsletter.

Further Declines in Biodiversity for the 21st Century

Biodiversity will continue to decline during the 21st century if business continues as usual. according to a new study published online for the journal Science , which includes Rashid Sumaila and former Sea Around Us Project members William Cheung and Sylvie Guenette as co-authors, and was timed with the COP-10 meeting on Biodiversity in Nagoya, Japan. Conservation efforts have slowed declines; the paper predicated the rate of decline in vertebrates would have been at least one-fifth higher in their absence. But they are not sufficient so far. The team also showed that declines could be further slowed if fundamental changes are implemented, such stopping the current practice of providing harmful subsidies that result in the over-exploitation of biological resources.

Biodiversity will continue to decline during the 21st century if business continues as usual. according to a new study published online for the journal Science , which includes Rashid Sumaila and former Sea Around Us Project members William Cheung and Sylvie Guenette as co-authors, and was timed with the COP-10 meeting on Biodiversity in Nagoya, Japan. Conservation efforts have slowed declines; the paper predicated the rate of decline in vertebrates would have been at least one-fifth higher in their absence. But they are not sufficient so far. The team also showed that declines could be further slowed if fundamental changes are implemented, such stopping the current practice of providing harmful subsidies that result in the over-exploitation of biological resources.

Reference: Henrique M. Pereira, Paul W. Leadley, Vânia Proença, Rob Alkemade, Jörn P. W. Scharlemann, Juan F. Fernandez-Manjarrés, Miguel B. Araújo, Patricia Balvanera, Reinette Biggs, William W. L. Cheung, Louise Chini, H. David Cooper, Eric L. Gilman, Sylvie Guénette, George C. Hurtt, Henry P. Huntington, Georgina M. Mace, Thierry Oberdorff, Carmen Revenga, Patrícia Rodrigues, Robert J. Scholes, Ussif Rashid Sumaila, Matt Walpole (2010) Scenarios for Global Biodiversity in the 21st Century Science .