Post-doctoral research fellow Ashley McCrea Strub and Daniel Pauly report on their recent efforts to help artist Maya Lin on her latest project on shifting baselines. They explain in the newsletter and below:

In February, Dr Pauly was contacted by Maya Lin, esteemed artist and architect best-known for designing the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial in Washington D.C. She is creating an exhibit to illustrate severe declines in species due to human exploitation, and asked Daniel if the Sea Around Us could provide ideas and information for a fish species. When considering overfishing and the collapse of fisheries, Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) is typically one of the first species that springs to mind. Cod occurs throughout the North Atlantic, along the shores of the first countries to develop industrial fisheries, notably England. The different cod stocks, (e.g., in the North Sea), are generally in parlous states, and those of the Northwestern Atlantic, off the coast of the United States and Canada, are no exception. Indeed, the collapse of eastern Canadian stocks off the coast of Newfoundland in 1992 had devastating economic, social and ecological consequences still visible today.

At the end of the last ice age, nearly 10,000 years ago, the availability and expansion of capelin and herring following the retreat of sea ice provided an abundant food source enabling the proliferation of Atlantic cod in the Northwest Atlantic (Rose 2007). The great abundance of this predator in ecosystems had a dominating influence over the community. Historical records indicate that massive populations of this predominantly bottom-feeding species were targeted by fisheries as early as the 15th century (Hutchings and Myers 1994). Technological advances allowed fisheries for cod to develop from hook-and-line to cod traps in the 1860s, the latter becoming larger and more efficient over time. The traps were then complemented by gill nets, but the key change was the introduction of bottom trawling early in the 20th century in New England as well as during the mid-20th century in Eastern Canada. As the vessels supporting these various domestic operations grew in size and power, distant-water factory trawlers, mostly from Europe, but some from as far as East Asia, were added to the fishery and generated catches in excess of 800,000 tonnes in the late 1960s and early 1970s. However, Atlantic cod is a relatively long-lived, slow growing species whose productive capacity could not keep up with the increasing rate of mortality due to fishing. As the great majority of spawning adults were packed into ships’ freezers, catches began to decline. By 1975, Canada and the United States declared national jurisdiction over what later became their 200 nautical-mile ‘Exclusive Economic Zones’, indirectly claiming ownership over the dwindling cod stocks and forcing out foreign fleets. The reduction in fishing, and recovery of cod that followed, was short-lived as overly optimistic fishery management measures and excessive subsidization led to record-low levels of biomass and a resultant fishing moratorium on the largest Canadian stocks in 1992. Despite significantly reduced fishing pressure, most stocks of cod in the Northwest Atlantic are still struggling to rebuild, and remain classified as ‘overfished.’

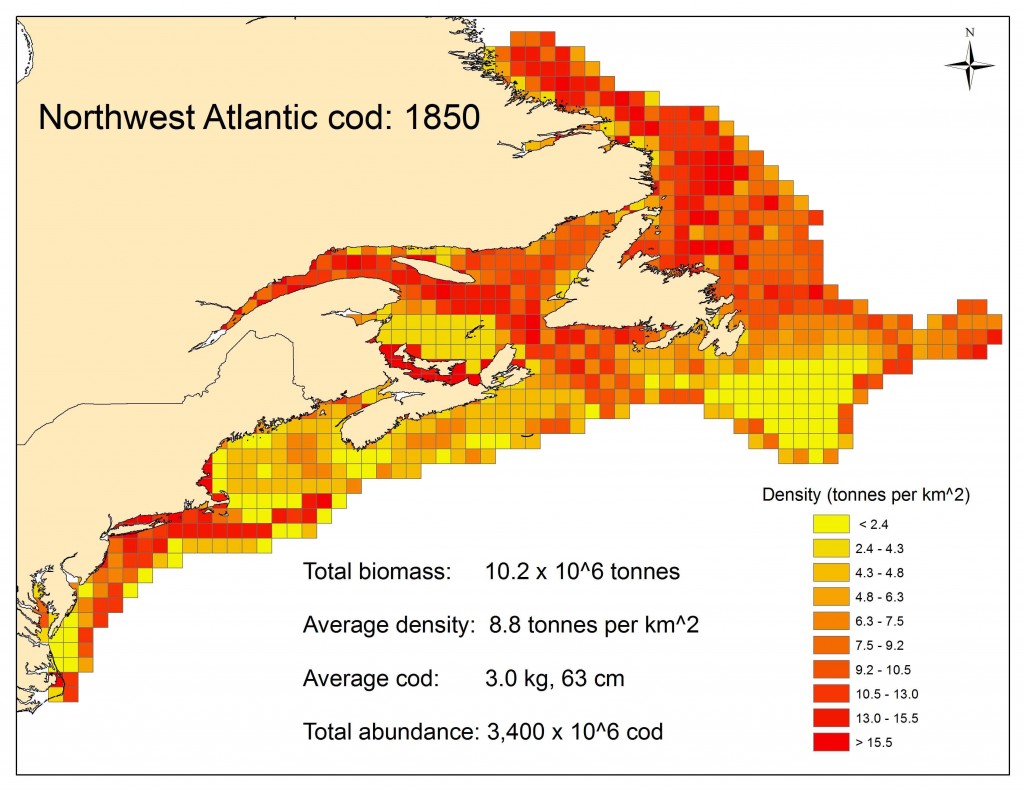

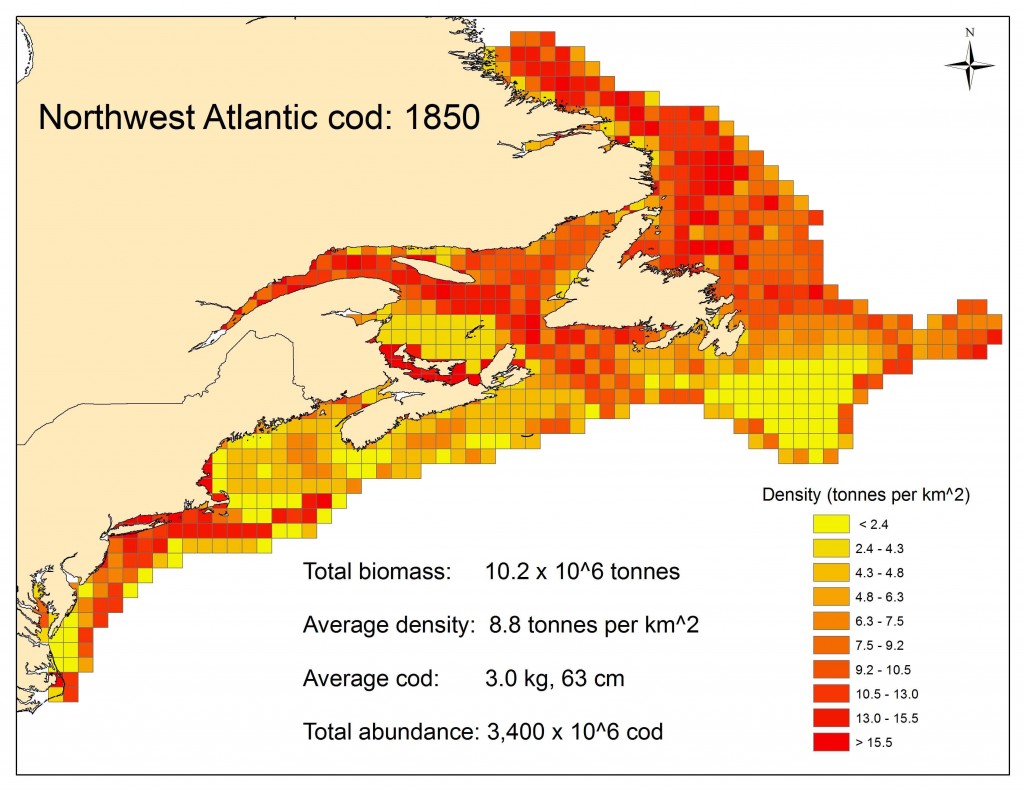

To help Maya Lin with the creation of her art exhibit, we conducted a study to help us better understand the extent of overfishing and the recent state of Atlantic cod off the eastern coast of Canada and the U.S., relative to a time when this species was still the most abundant predator in the region. To begin, information regarding the relative abundance of Atlantic cod from the northern coast of Labrador to Cape Hatteras, North Carolina was obtained from the global fisheries database developed and maintained by the Sea Around Us Project at the Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia. Using historical spatial distribution data, as well as biological data including preferred depth, latitudinal limits and proximity to critical habitat, the likely geographic distribution of over 1000 commercially fished species, including Atlantic cod, has been defined (Watson et al. 2004; Close et al. 2006). This database enables the production of maps illustrating the relative abundance or likelihood of locating a particular species in a spatial grid of cells measuring 0.5° latitude by 0.5° longitude. Populating such a map to reflect the actual numbers or biomass of fish present in a given area during a specific time period is then possible given suitable data on fish density.

Information regarding the size of the Atlantic cod population in approximately 1850 was gathered from an analysis of mid-19th century logbooks maintained by a handline fleet that fished the Scotian Shelf, the centre of the range of Northwestern Atlantic cod, prior to the industrialization of fishing (Rosenberg et al. 2005). Due to the relatively low level of fishing pressure, this population was assumed, for the purposes of this study, to be relatively close to its unfished maximum at this time. Using detailed, spatially specific logs, Rosenberg et al. (2005) estimated the historical biomass of cod on the eastern and western Scotian Shelf (encompassing an area of over 160,000 km2) as 1.26 million tonnes. Accordingly, the average biomass density of cod on the Scotian Shelf in 1850 was approximately 8 tonnes per km2. In the absence of similar information for other areas, this estimate of average density was assumed to be representative of the entire region considered here. To create a map of the density of cod biomass in 1850, this average density was scaled according to spatially specific estimates of the relative abundance of cod, resulting in values defining the density of cod in each grid cell included in the study region.

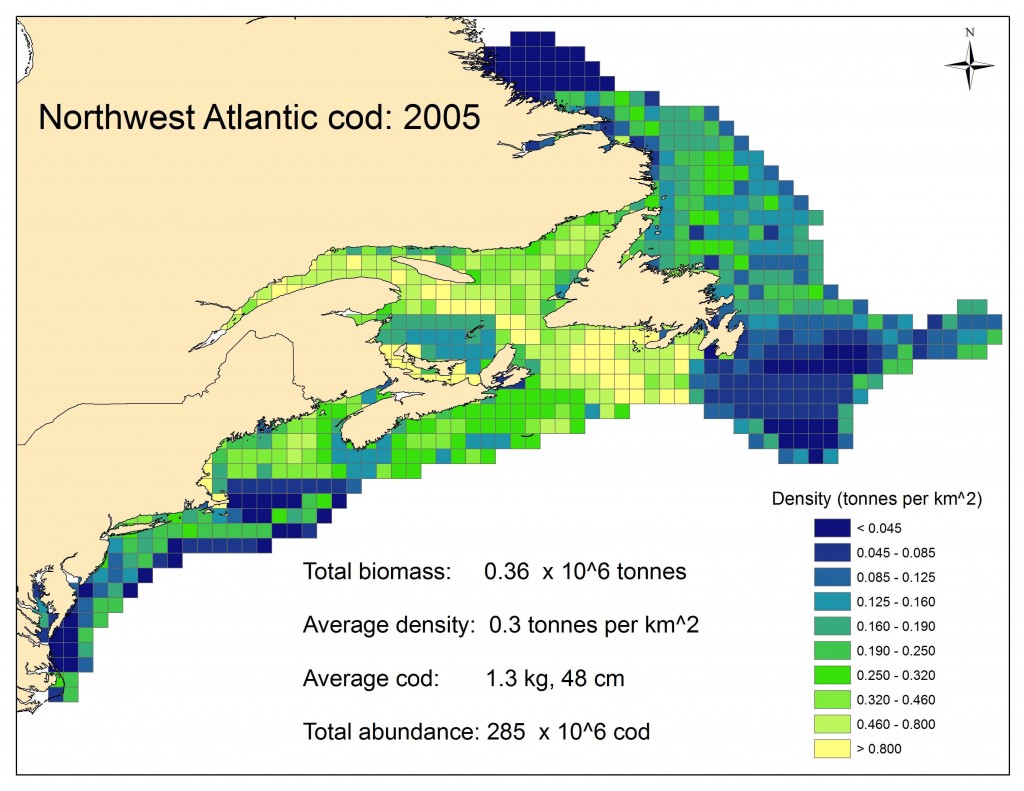

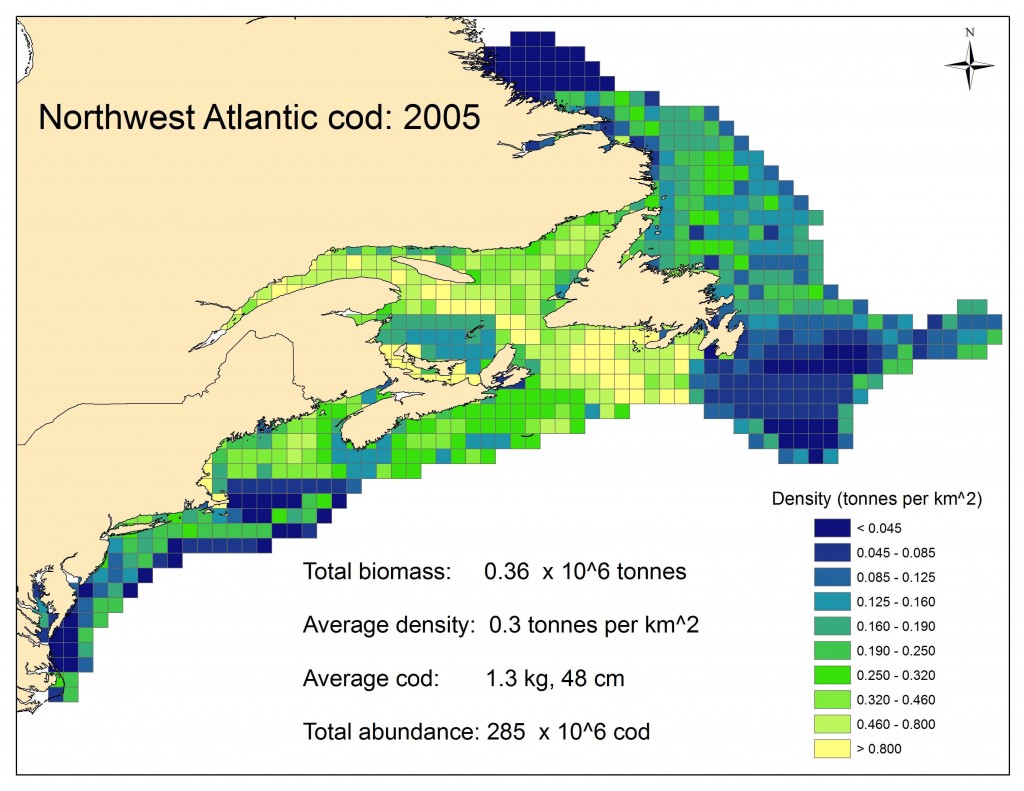

To estimate recent biomass, the results of stock assessments conducted by the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) were assembled. As stock assessments have not been performed for every Northwestern Atlantic cod stock in the past year, and to avoid uncertainty associated with the most recent assessments, biomass estimates for 2005 were collected for each stock.

This process enabled the production of maps of cod biomass density as well as the approximation of total biomass for the years 1850 and 2005. As estimates of fish population size are typically based partially or wholly on records of catches from previous years, the population considered usually includes those individuals that are vulnerable to fishing gear (e.g., age 3-4+ Northwest Atlantic cod) or sexually-mature individuals (i.e. the spawning stock, age 5-7 in the case of Northwest Atlantic cod). Unless otherwise noted, population size estimates calculated in this study refer to the portion of the Northwest Atlantic cod population vulnerable to fishing.

In addition to the total size of the Northwest Atlantic cod stock during these contrasting time periods, the change in size of an ‘average cod’ since 1850 due to the effects of (over)fishing was also estimated. Calculating average cod size first required biological information describing the rate at which this species grows in length and weight over its lifetime (Sinclair 2001). When used in conjunction with the approximate total mortality rate (due to both natural causes and fishing) during 1850 and 2005, the average length and weight of a cod during each of these time periods was calculated1.

The maps created as a result of this study provide very different pictures of the abundant cod population in the Northwestern Atlantic prior to the onset of industrial-scale fishing in 1850 (Figure 1) and the severely depleted population following decades of intense fishing pressure in 2005 (Figure 2). In 1850, the total biomass of Atlantic cod was approximately 10.2 billion (10.2 x 106) tonnes. By 2005, it was estimated that this biomass had decreased by over 96% to 0.36 x 106 tonnes. Thus, the average density of cod biomass across the study region fell from 8 tonnes/km2 to 0.3 tonnes/km2, 3.5% of the initial value.

Fishing not only reduces population abundance, but also the size of an average fish in the population. Thus, in 1850, the average cod more than 3 years in age would have been about 63 cm in length and weighed 3.0 kg, while the average mature adult was 78 cm and weighed nearly 6 kg. By 2005, the size of an average cod greater than age 3 had fallen to 58 cm and 1.3 kg, and an average mature cod measured 68 cm and weighed 3.6 kg. It is important to note that the ‘average cod’ size in 1850 presented here is conservative and may be an underestimate of the true average size during this time period. This is due to the fact that most studies of Northwest Atlantic cod growth were relatively recent and parameter estimates were based on fish sampled from stocks already affected by many years of fishing. Thus, potential fisheries-induced changes in growth rate were not considered here.

Knowledge of population biomass and average weight enables an approximation of the number of Atlantic cod during each time period. In 1850 the population of Atlantic cod in this region was composed of roughly 3.4 trillion (3,400 x 106) individuals, and had decreased by approximately 92% by 2005 (i.e., to 285 billion or 285 x 106 cod). As younger, smaller individuals tend to be more abundant in a population, particularly in the case of heavily fished populations, merely analyzing the change in abundance of cod masks the true effects of overfishing; biomass was nearly 30 times lower in 2005 relative to 1850, while the abundance of cod was only 12 times lower in 2005 compared to 1850.

At a time when healthy, under-exploited fish stocks appear to be the exception rather than the rule across the globe and the ‘shifting-baselines’ syndrome has become widespread, numbers such as those presented here provide a perspective on the extent of human impacts on species and ecosystems, and of what we have lost. The data and maps generated as a result of this study will be used by Maya Lin to guide the design of her upcoming exhibit, providing an exciting vehicle for the Sea Around Us Project to communicate our work to a broad audience.

References

Close, C., W. Cheung, S. Hodgson, V. Lam, R. Watson and D. Pauly. (2006). Distribution ranges of commercial fishes and invertebrates, p. 27-37 In: Palomares, M.L.D., K.I. Stergiou and D. Pauly (Editors). 2006. Fishes in Databases and Ecosystems. Fisheries Centre Research Reports 14(4).

Hutchings, J.A. and R.A. Myers. (1994). What can be learned from the collapse of a renewable resource? Atlantic Cod, Gadus morhua, of Newfoundland and Labrador. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 51: 2126-2146.

Rose, G. (2007). Cod: An Ecological History of the North American Fisheries. Breakwater Books LTD., St. John’s, Newfoundland. 580 pp.

Rosenberg, A.A., W. J. Bolster, K.E. Alexander, W. B. Leavenworth, A.B. Cooper, and M.G. McKenzie. (2005). The history of ocean resources: modeling cod biomass using historical records. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 3: 84-90.

Sinclair, A.F. (2001) Natural mortality of cod (Gadus morhua) in the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence.ICES Journal of Marine Science 58:1-10.

Watson, R., A. Kitchingman, A. Gelchu, and D. Pauly. (2004). Mapping global fisheries: sharpening our focus. Fish and Fisheries 5: 168-177.

Endnote: Cod were assumed to grow in length according to the von Bertalanffy growth equation, where Linf = 118 cm, K = 0.11 year-1, and t0 = -0.44 yrs. (Sinclair 2001). Total length (cm) was then converted to weight (kg) using the relationship W = 0.0081*L3.03 (www.fishbase.org). The natural mortality rate (M) was assumed to equal 0.2 year-1. Fishing mortality (F) for the entire study region was calculated using the mean F reported by each stock assessment, weighted according to the estimated biomass of each assessed stock, resulting in an estimate of 0.3 year-1 for 2005.

Fish catches in Madagascar over the last half-century are double the official reports, and much of that fish is being caught by unregulated traditional fishers or accessed cheaply by foreign fishing vessels. Seafood exports from Madagascar often end up in a European recipe, but are a recipe for political unrest at home, where two-thirds of the population face hunger. These are the findings of a recent study led by the Sea Around Us Project in collaboration with the Madagascar-based conservation organisation Blue Ventures. The research, published online this week in the journal Marine Policy, used existing studies and local knowledge to estimate total fisheries catches between 1950 and 2008. Read the full study here and the press release here.

Fish catches in Madagascar over the last half-century are double the official reports, and much of that fish is being caught by unregulated traditional fishers or accessed cheaply by foreign fishing vessels. Seafood exports from Madagascar often end up in a European recipe, but are a recipe for political unrest at home, where two-thirds of the population face hunger. These are the findings of a recent study led by the Sea Around Us Project in collaboration with the Madagascar-based conservation organisation Blue Ventures. The research, published online this week in the journal Marine Policy, used existing studies and local knowledge to estimate total fisheries catches between 1950 and 2008. Read the full study here and the press release here.