The Great Wall of China is not the only thing you can see from space. Fish farming cages are clearly visible through Google Earth’s satellite images and University of British Columbia researchers have used them to estimate the amount of fish being cultivated in the Mediterranean.

The Great Wall of China is not the only thing you can see from space. Fish farming cages are clearly visible through Google Earth’s satellite images and University of British Columbia researchers have used them to estimate the amount of fish being cultivated in the Mediterranean.

The study, published yesterday in the online journal PLoS ONE, is the first to estimate seafood production using satellite imagery.

“Our colleagues have repeatedly shown that accurate reporting of wild-caught fish has been a problem, and we wondered whether there might be similar issues for fish farming,” says lead author Pablo Trujillo, an Oceans Science Advisor for Greenpeace International, who conducted the study while a research assistant at the UBC Fisheries Centre.

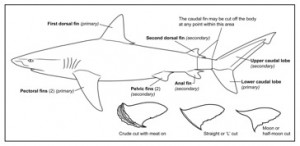

“We chose the Mediterranean because it had excellent satellite coverage and because it was of personal interest,” says Chiara Piroddi, co-author and an ecosystem modeler at the UBC Fisheries Centre. “We hand counted 20,976 finfish cages and 248 tuna cages, which you can differentiate due to their extremely large size – each tuna cage measured at more than 40 metres across.”

Almost half the cages were located off the coast of Greece and nearly one-third off of Turkey – and both countries appear to underreport their farmed fish production. The researchers note that not all areas had full satellite coverage – for instance, images were missing for large portions of the coasts of France and Israel, for reasons the authors do not fully understand.

Combining cage counts with available information on cage volume, fish density, harvest rates, and seasonal capacity, the research team estimated ocean finfish production for 16 Mediterranean countries at 225,736 tonnes (excluding tuna). The estimate corresponded with government reports for the region, suggesting that, while there are discrepancies at the level of individual countries, overall, the Mediterranean countries are giving accurate counts.

“The results are reassuring, and the methods are inspiring,” says co-author Jennifer Jacquet, a post-doctoral researcher with UBC’s Sea Around Us Project. “This shows the promise of Google Earth for collecting and verifying data, which means a few trained scientists can use a freely available program to fact-check governments and other large institutions.”

Trujillo adds that Google Earth, with its high-resolution images and consistent time series, can be a powerful tool for scientists and non-governmental organizations to monitor activities related to ocean zoning and capture fisheries.

See some coverage of the work at The Scientist.