Dyhia Belhabib gives a presentation at the West Africa capacity-building workshop at UBC

On the third day of the West Africa capacity-building workshop researchers narrowed down subject areas to analyze — areas, they agree, that are affecting all countries in the West Africa sub-region, and therefore, need to be confronted through nation-to-nation collaboration.

Dr. Dyhia Belhabib, who organized and is coordinating the two-week workshop, said that four topics have been decided upon. These are, broadly, climate change, marine protected areas, illegal fishing, and governance. A different group of researchers will look at each of the topics.

For climate change, it is important to understand the resilience of artisanal fisheries in the facing of changing temperatures, and mitigation steps that can be taken. Regarding marine protected areas (MPA’s), the researchers will look at tools for assessing and evaluating their effectiveness, and how MPA’s create resilience in local communities. A group of researchers will study whether enforcement is an effective measure to recover value lost by IUU fishing. And finally, another group will study the need for better data in facilitating effective governance.

The workshop is a unique opportunity for researchers from multiple West African countries to share data and experience.

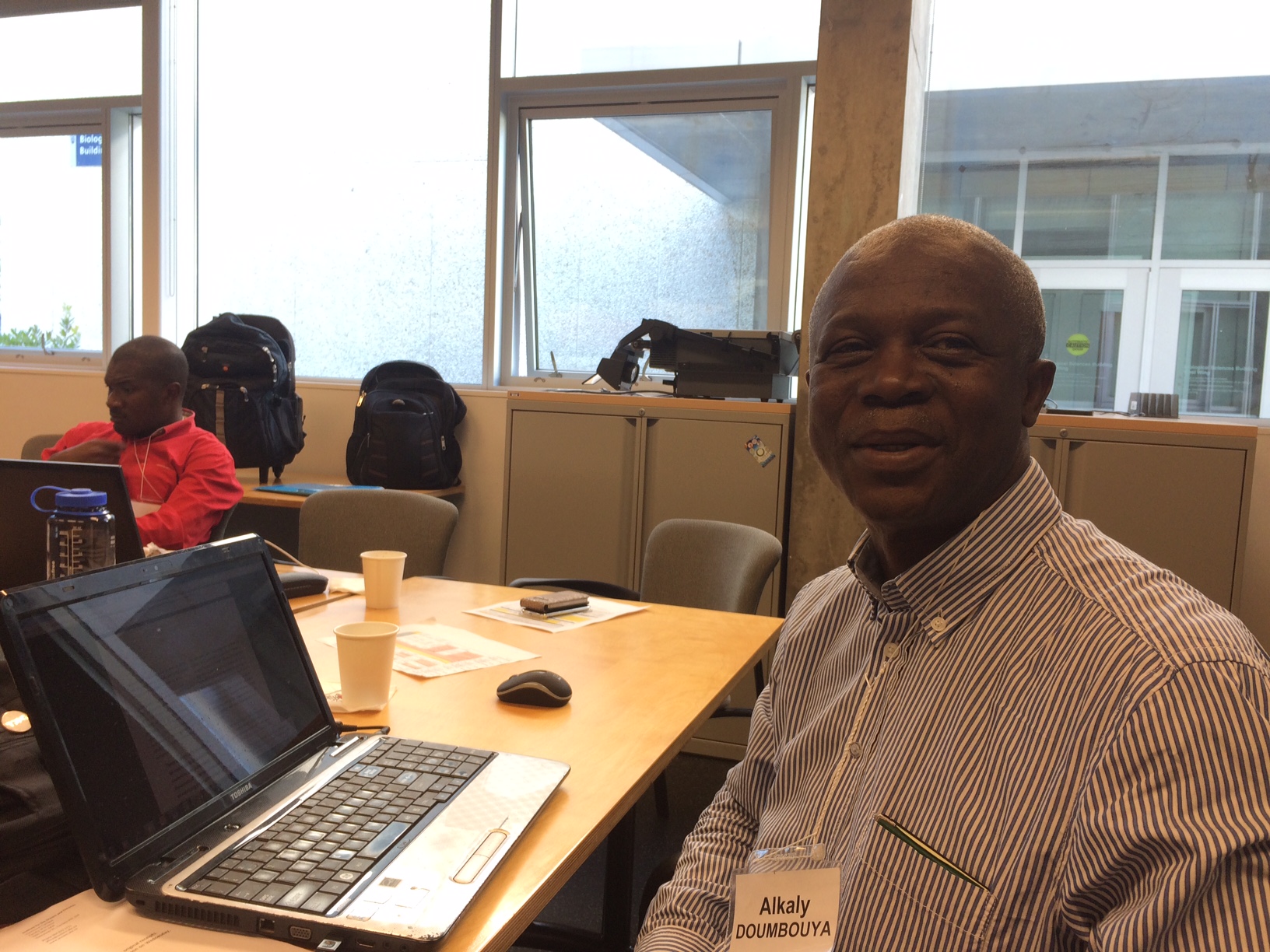

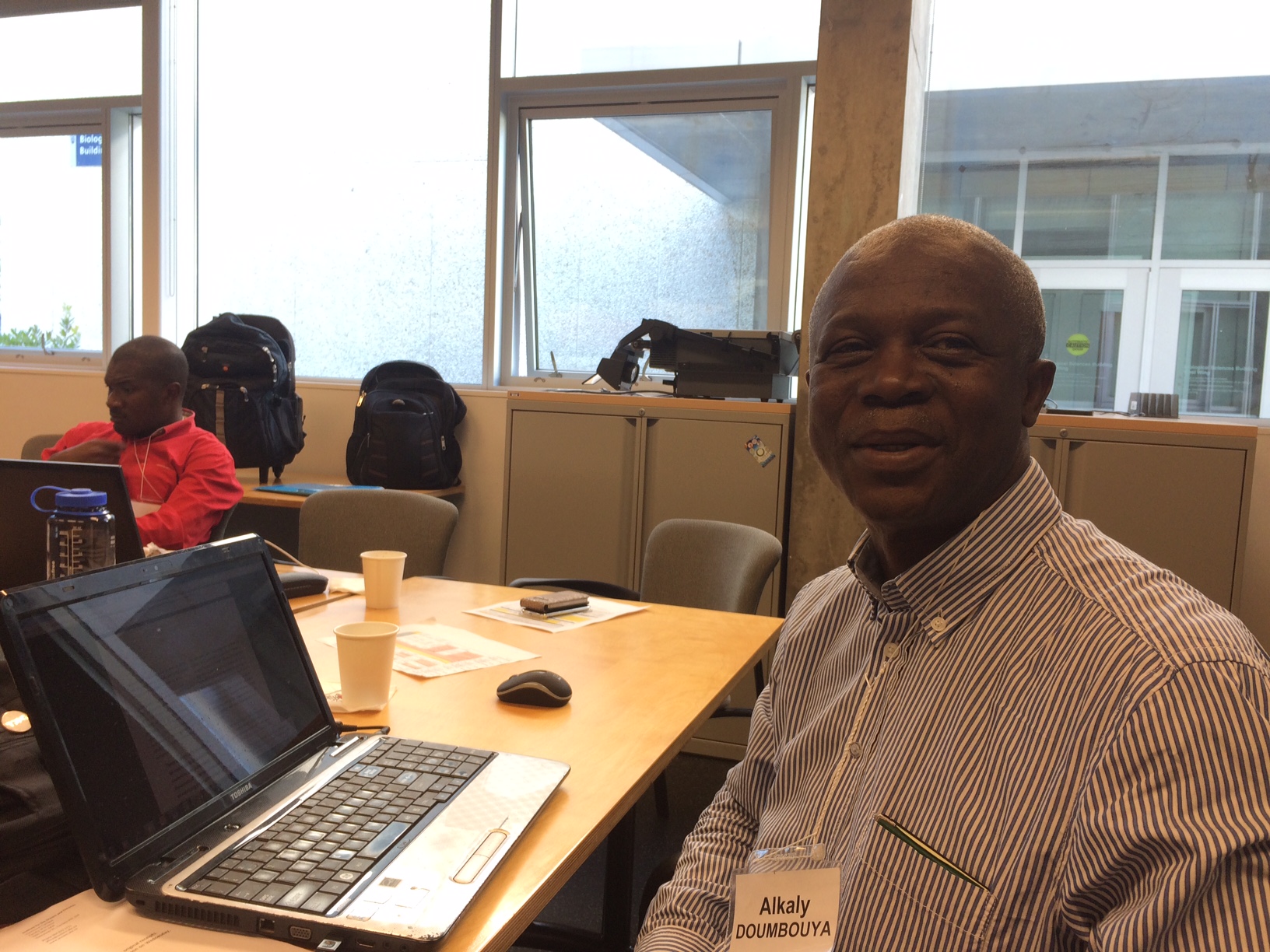

Alkaly Doumbouya, a Senior Scientist at Guinea’s centre for fisheries science, believes finding data to combat these issues is difficult — yet meeting with researchers from other countries, and with the Sea Around Us, can help fill in the gaps.

“It is not easy to find data because data is rarely made public. And the ministries do not work well together,” he says about Guinea, where he is from.

Alkaly Doumbouya, Guinea. Senior Scientist at the country’s fisheries research centre.

To help with this issue, other members in the workshop are helping to find relevant data, he adds.

Dyhia, who is facilitating the dialogue among the various groups, is emphasizing the sharing and collaboration of information. “Every group is contributing to other groups” she says.

Doumbouya believes Dyhia is essential to the workshops functioning. “Dyhia has travelled to all these countries and understands the issues there,” he says.

Doumbouya’s group in the workshop is looking at illegal fishing. He says there is a lot of data on the number of illegal boats caught, and how much fish they have caught, as well as the fines they have paid — yet the problem is that all the data is spread through various institutions in his country, Guinea. He hopes that countries in the sub-region can come together, share data, and create standardized rules to measure the effects of illegal fishing, and enforce rules prohibiting it.

The workshop will break after lunch for a trip to the Vancouver Aquarium. Updates to come.