For International Women’s Day 2024, we want our audience to get to know the women in the Sea Around Us in a context that goes beyond science and their professional selves.

Category: Contact

UBC researchers launch Africa-UBC Oceans & Fisheries Visiting Fellows Program

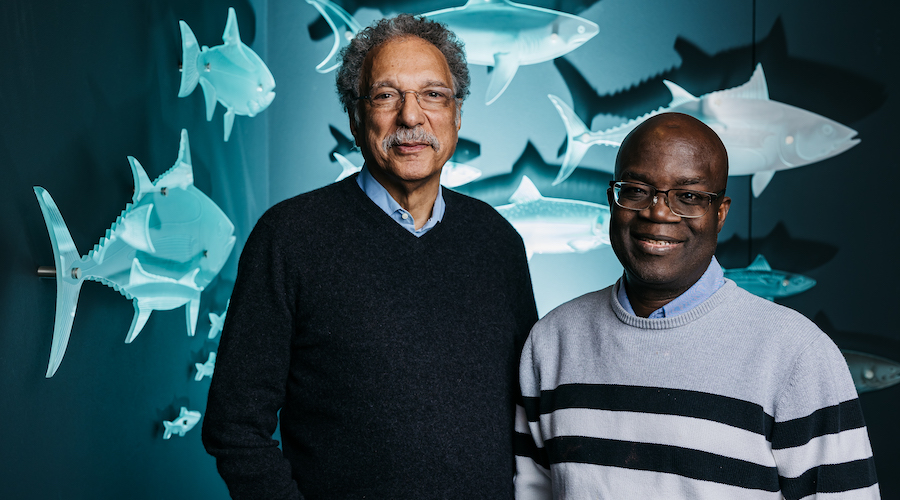

Dr. Daniel Pauly and Dr. Rashid Sumaila have launched the Africa-UBC Oceans & Fisheries Visiting Fellows Program. Photo by Kim Bellavance, Tyler Prize.

University of British Columbia researchers Dr. Rashid Sumaila and Dr. Daniel Pauly have launched the Africa-UBC Oceans & Fisheries Visiting Fellows Program, whose goal is to inspire exceptional young African researchers to develop ocean and freshwater sustainability solutions.

The fellowship is aimed at early-career academics from sub-Saharan African universities and research institutes who are interested in engaging with leading researchers at UBC’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries to facilitate diverse, equitable, mutually beneficial research collaborations.

Scientists push WTO to ban fisheries subsidies

Shrimp trawler. Photo by Stephanie Lee, Flickr.

Fisheries scientists and marine biologists working in all corners of the world, from Canada to Australia, from Malaysia to Nigeria, and from Brazil to Monaco, are once again making a call to the World Trade Organization (WTO) to approve additional regulations that eliminate harmful fisheries subsidies.

Unilateral efforts to combat illegal fishing may spur piracy in certain regions

Certain policies and policing measures taken by countries to combat illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing drive local actors to engage in piracy, new research has found.

A poster to celebrate the Sea Around Us 25th anniversary

In July 2024, the Sea Around Us turns 25 years old.

During this quarter-century, the project has been dedicated to examining the impacts of fisheries on the marine ecosystems of the world. It has been and remains instrumental in ocean conservation.