Economist Rashid Sumaila recently responded to the paper by Trevor Branch and colleagues in the journal Nature:

Economist Rashid Sumaila recently responded to the paper by Trevor Branch and colleagues in the journal Nature:

The trophic fingerprint of marine fisheries’ (Nature, 468, 431-435, 2010), has intensified the debate on how best to measure the impact of commercial fishing on ocean biodiversity: Is catch data useful in telling us what is happening in the ocean or do we need stock assessment information in order to say something meaningful? As an economist, I cannot contribute to this debate but I can ask some questions: What conclusion does one come to if one uses one or the other of these approaches?If one ends up with the same conclusion then the debate is only of academic interest. If the conclusions reached are different, what are the potential costs to the world should one or the other be incorrect? In general, proponents of the use of stock assessments for measuring the ‘health’ of ocean fish populations, led by Ray Hilborn of the University of Washington, conclude that ocean fish populations are doing just fine, while those who use catch data, spearheaded by Daniel Pauly of the University of British Columbia, come to the conclusion that global fish stocks are in bad shape. Depending on which of these two camps wins the argument, the world would either stick to the status quo and continue to manage global fisheries as we currently do, or the world community would double its efforts to manage global fisheries sustainably. Should the former conclusion turn out to be incorrect, the world would have saved some costs by continuing to fish without further management restrictions, with the consequence that ocean biodiversity would be eroded further, thereby supplying less and less fish with time. On the other hand, if the latter turns out to be incorrect, the world would have incurred unnecessary cost due to stricter management but would have an ocean rich in biodiversity that is capable of supplying fish into the future.

Read more on this issue here.

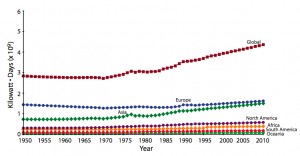

A new study by Sea Around Us Project members examines the global trends in fishing effort from 1950 to 2006 using FAO fisheries data. The analysis confirmed global fishing effort is increasing and that effort is led by Europe and Asia. Trawlers contribute a major fraction of global fishing effort, as do vessels greater than 100 gross registered tons. But the study also notes that there are many limitations to the data, such as the absence of effort data for many countries and the issue of illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing. This means that the World Bank estimate of $50 billion in fisheries losses due to overcapacity is conservative.

A new study by Sea Around Us Project members examines the global trends in fishing effort from 1950 to 2006 using FAO fisheries data. The analysis confirmed global fishing effort is increasing and that effort is led by Europe and Asia. Trawlers contribute a major fraction of global fishing effort, as do vessels greater than 100 gross registered tons. But the study also notes that there are many limitations to the data, such as the absence of effort data for many countries and the issue of illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing. This means that the World Bank estimate of $50 billion in fisheries losses due to overcapacity is conservative.